Through sociocracy you can design feedback systems so everyone in your community knows what is going on and can be heard on matters that affect them. In this webinar, recorded on December 2022, Sociocracy for All’s Ted Rau and Jerry Koch-Gonzalez share in dept knowledge about using consensus to foster a sense of harmony and connection in your group.

Far from the intentional community horror stories you may have heard, a sociocratic meeting is manageable and calm. There are opportunities for every person in the room to express their thoughts and be heard.

To learn more about Sociocracy, join Ted Rau and Jerry Koch-Gonzalez in the online course Sociocracy for Communities.

They will cover how to optimize group listening, divide decision-making authority into meaningful chunks, and empower people to act with clarity. You’ll learn how to implement sociocracy correctly, with adaptations for your community’s specific needs.

Transcript

Ted Rau: Good governance is basically silent, right? Good governance is such that you hardly even notice it. So all the processes around rounds, consent, and clarifying questions, and this and that, once it's going, it's just something that you do. It's not so much that you notice that there's this whole other layer of magic process, it just looks like normal people talking to each other and everybody having a different way of doing it and being clear about what we're talking about. And that is typically news to people that it's more the absence that they will notice, the absence of drama, the absence of being interrupted, all of those things. So good governance is simply smooth and silence. That's what what I'm striving for. Because if it's smooth and silent, then we can just focus on what we want to do with each other instead of having to focus on other drama between us.

Lauren: All right. So greetings to everyone joining us on Zoom as well as Facebook Live. This is me using social ocracy to support harmony and connection webinar with Sociacracy for All. Ted Rau and Jerry Koch-Gonzalez. A warm welcome to you all. So my name is Lauren and I'm the program director here at the Foundation for Intentional Community. And I am your host for this session. So if you encounter any tech issues or otherwise need some assistance, please don't hesitate to send me a private message in the chat and I will be more than happy to help you out. All right, now I'm going to introduce our presenters, Ted Rau: and Jerry Koch-Gonzalez.

Ted is part of Sociocracy for All (SoFA) an international organization he co-founded with his colleague Jerry Koch-Gonzalez in 2016. SoFA is now, a growing international movement service organization that provides resources, training and networking for sociocracy practitioners. Ted coauthored The Sociocracy Handbook: Many Voices, One Song and has taught Sociocracy workshops in several countries, including the United States, Brazil, the United Kingdom and Italy. Ted is transgender, and his experience of seeing gender dynamics from both sides has influenced his thinking and perception. Ted has five children and has been a resident of Pioneer Valley Cohousing in Massachusetts since 2012.

Jerry helps companies and organizations implement sociocracy to create adaptive and effective organizations where all members voices matter. He is a consultant and certified trainer in both Dynamic Governance, for Sociocracy, and Compassionate Communication, also known as NVC. He has been a board member of the Institute for Community Economics, United for a Fair Economy, in Class Action, and a trainer with the Movement for a New Society, the National Coalition Building Institute, Diversity Works, Cambridge Youth Peace and Justice Corp's Leslie College Center for Peaceable Schools, Boston College Center for Social Justice, the Association for Resident Controlled Housing, and Spirit in Action. And with that, I'm going to hand it over to Ted and Jerry. Thank you both for sharing your wisdom with us today. And over to you, gentlemen.

Ted Rau: Thank you. And thank you for having us. So I'm going to start. This is today about sociocracy to support harmony and connection. So here we are. You already heard about Jerry and me, but for the sake of the people who want a visual for that. There you go. One little comment is here's an update. Pioneer Valley Cohousing is the community where we live, but it now has a new name, Cherry Hill Cohousing. So we already updated that, but we didn't tell you, Lauren.

About this event. As Lauren was alluding to, it's not always easy to be in a community together, and we will look at several topics that create tensions here and there, and some of the answers that sociocracy is giving. So sociocracy is the same as dynamic governance, they're used interchangeably. And we'll just weave our explanations of how it works here and there into the things that we're saying. I also want to be clear that sociocracy is not a kind of all-powerful tool. It helps with a lot of things around governance, but it really also needs, of course, strong communication with conflict resolution and so on and we'll only focus on the governance angle of that piece. So we will approach it from the governance lens and look at all the other things where they might come in. But really that is our focus, and we will go through these five tensions and just take turns and also tell a few stories along the way that show what we're talking about. So Jerry is going to be first, with the first tension.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: Okay. So the first: who decides what? One of the aspects of sociocracy is we work in teams and small groups that have a particular focus, and being very clear: where does the area of responsibility for our team end, and the area of responsibility for a different group start? So if you're trying to create community, you might have an outreach group, marketing group, and a sales group - people who are actually buying into the community. So you want to have that distinction: where does the people who are trying to do the outreach and attract people to the community, then turn over the people they have attracted to the community to the group that's going to take the next step?

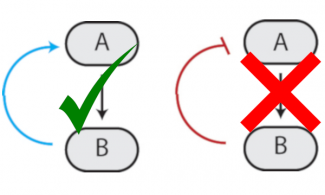

So you want not to have the overlaps, as you see in the very top little diagram where there's two teams that have overlapping functions and so they can get confused. You have also the possibility of two teams with a missing link in between. For example, in my community, when sometimes the membership circle would bring in a new member, they sometimes didn't tell the finance people that the new member had arrived and could start collecting dues from that person. So there was a gap in communication there. So what we're looking for is teams that are really clearly connected to each other, the hand-off between one and the other as an issue moves through from one to another group in the work. And to the next slide.

Here is just kind of the standard diagram of what we would look at in sociocracy or dynamic governance about how we how we organize, how we are structured. In this frame you can see the top circle here we call the mission circle of the board, the coordinating circle and the different departments or sectors of your community, be they the people, the land, the machines and the buildings. So each one of these has their own domain of responsibility. And that's the piece that we were just talking about, the clarity of domains, of separating the different groups. If you're not clear on the domains of each group, then it's inevitable that you will wind up having conflict as you drop things, or you double do things, or you are doing things in different ways from each other. Now we'll take that to just stories about that.

Common house closing. You know, this is one of those that many of us who have a shared building and have dealt with Covid have had to decide, because now we as a community, we're a government that also has to decide whether to keep our facilities open or closed, masking or not. And there's been a number of different communities that have struggled over which team, or as a whole, gets to decide when, and how long, and in what conditions to close the common building. If you don't have a clear agreement on that, you are going to head into conflict. Another one is the community name. Let's see...why don't you tell the one about the junk car, Ted?

Ted Rau: So the junk car is an interesting little story. So in our community we have 40 apartment circuits like this. We happen to not have a mission circle like this. So imagine four circles, with sub-circles that take some part of the overall decision making. So one of those department circles is buildings and grounds, one of them is common house circles, one of them is community life, and then there's one for plants and animals and so on. So what happened one day was that somebody sent an email to the whole community on our listserve saying, I want to put my junk car at the end of the driveway. Can I do that?

In a sociocratic system asking the listener is always not the best idea, because ultimately some circle has that decision in its domain and will make a decision. So asking 100 people isn't a super useful. But what happened then was that, I was at that point the candidate coordinator of this coordinating circle, and so I took that topic - because it wasn't so clear to me where it would belong, who would decide that, in which domain it would be - so I took it and I asked - fortunately, a meeting was just coming up - I asked this what's also called the General Circle, Coordinating Circle, and you can see two people from each of these department circles is present. So I had two people from the plants and animals circle, two people from common house, two people from community life, and two people from buildings and grounds. And I asked them, who's going to decide about the junk car? And in that case, nobody really knows. So we had to just make a fairly arbitrary decision.

But the cool thing about that was that now each of the groups, each of the circles or the people from those circles, were able to give feedback on what needs to be considered about the junk car. What was fascinating to me about that is that I hadn't been able to predict any of it. So, for example, community life, somebody said, Oh, this is going to be, you know, our community we like. That's kind of what people see on the public road. And the only thing they see about this community is a junkyard that's not so super inviting. We don't like it, but it's a pretty, you know, only very temporary. Then the people from plants and animals were like, wait, that's right next to the raspberry patch. Is this oil? Is this thing dripping oil? Because we've been working hard on having organic raspberries here, a junkyard is the last thing we want.

And then buildings and grounds that is also in charge of the roads was saying, wait, is this going to block emergency access? Because that's in our domain. We just want to make sure that doesn't happen. So it was really interesting to see how it touched on several issues. And because we had those links, we call them delegates and leaders here because we had them present, we were able to resolve it very quickly and we then didn't decide whether the junk car would be allowed, but we decided who would take care of it and decided. And I think back then we put it into Community Life. Everybody consented, Community Life can decide and then Community Life just made a very quick decision. And it shows you how we can have a mechanism to decide who decides and that is very clear, so that if there's a gap, if you've not predicted that it would ever be a junk car, you can close that gap together and really still be in alignment, and have actually a very clear image about going forward who decides what.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: And the community name. This is our story as well. As we shifted from Pioneer Valley Cohousing Communities to Cherry Hill Co-housing, it started off with a small group of people who self-appointed that they wanted to work on this topic. And what evolved over time was the clarity that there was lack of clarity of who was going to be a surrogate to make the decision about the change of name. So if you think of a group of 50 people in a community, or 70 people in the community, trying to come to an agreement about a name, you don't have a basis of reasoning. It's you know, I like this. I like Cherry Hill. I like something else. I like Full Circle Cohousing. I like...You know, it's such a personal choice, your preference around names.

But the name affects everybody in the community. So there are a number of people who said, well, this decision has to be made by the whole community together. And of course, this was happening during Covid time where we couldn't meet in person. So that was also a challenge. It was harder to read each other emotionally. How would a group of 70 people make that decision? So it was unlikely that we would be able to make a simple decision by consensus or consent in such a large group. So we had to figure out what was the legitimacy of the decision making process. So we had to come up with a consent about the process that we were going to use to make the decision.

And we started off trying to have our coordinating team make that decision. And then that that was challenged again, because we were not clear about the boundary between the coordinating circle and the full circle authorities. And so we ultimately needed to get the whole community to accept the decision making process that we were going to use. Then we could go through the process and eventually make that decision. So this is one of this is one of the reasons we like sociocracy, where we really try to avoid as much decision making as possible from the full plenary, and into the coordinating circle or into one of the department circles where a smaller group can take responsibility for the decision and still get the feedback that would be useful to make a decision that would be supported by most folks in the community.

Ted Rau: My turn, I think. Good decision making: so the basic idea of decision making that is kind of baked into how sociocracy is built is that only decisions are good decisions that have really been well considered. So when many people have been able to be heard in a decision, then it's possible to make a decision that lasts a lot longer. Unless we know that we kind of made a made a decision for the short term and we're willing to improve it. But sustainability really comes when voices are heard, right? If somebody holds back on information because they're too shy to speak up, but they know that this thing that we're trying to decide is not going to work, that's simply not a good idea. So getting things out in the open and hearing other voices becomes one of the principles. It also has to be clear when a decision is made, I'll get to that in a moment. And it also has to be clear what happens if somebody disagrees. I also have a story for that, so let's look at that.

So the first story I want to tell is a story that I am aware of in a community, where there was a decision that needed to be made and two of the people abstained. And it was a pretty big deal, actually, in the group - that decision was a big deal. Two members abstained, didn't really say why and the rest I said, "Okay, whatever, if you abstain then the decision is simply made."

And then the decision was acted upon, which meant back then calling people and giving them a big piece of information. And as far as I know the information to those external people was passed on basically that evening after the meeting. And in the morning the two circle members who had abstained, woke up regretting abstaining. And then that left a little crisis in the group, actually, because the level of regrets was quite significant. But it had already happened. People were already informed. It was kind of already a done deal at that point. And the big learning for me about that one is it's simply not a good idea to have people abstain. And that is also something that doesn't happen in consent decision making.

You can object; if you don't have an objection, you consent. But there is no "decide this without me" kind of thing. And back then in that story, what would have helped us to hear from those two people, really say is there something that you're not comfortable with in this decision? Instead of letting them just not be part of the decision and kind of avoid the issue. It would have been better to hear it, because then we would have heard the issues, that then we heard after the fact when it was too late. Because ultimately, in my experience, those things do come up. The question is, do they come up when we can still do something about it or after? So abstaining is not a practice that that is being done in sociocracy for really good reasons, I find.

So we want everybody in a group in one of those circles, in those small groups, to have a voice in the decision making. And ask sometimes, even directly, each individual in a round. Sometimes it's just short like thumbs up and sometimes it's actually asking like "Jerry, do you consent to this decision?" And then the next person, and then the next person, so that we can be sure that we're not missing anything that people are sitting on.

Another one is a horror story, as I was part of a decision making that honestly baffled me quite a bit because it was supposedly a consensus decision. But what happened was that the facilitator asked a question, then waited for five seconds whether any of the 30 people in the room would say something and then said, okay. As I saw, as far as I read the room, everybody was okay with it. And I was absolutely shocked because I was actually not okay with it. But five seconds were not enough to kind of sort my my feelings and to raise my hand in a group of thirty people and say, "No, actually. No." And it was one of these examples for me where just reading the room is simply not enough for me. I want to have that clarity of: first, I want to be able to ask questions — I want to be able to say what I think, and I want to be asked explicitly, "Is this okay or not?" and not just assumptions being made. So often in these informal decision making methods, it's just lacking that level of clarity that I find supportive, if it's about hearing my voice. Jerry, do you want to tell this story?

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: Sure. Changing the function of a room. This was a situation in a co-housing community that had just adopted sociocracy. And so the common house circle was like "Great! Now we have authority to do some changes, to do some things in the common spaces." And practically the day after the decision had been made to adopt sociocracy, they went and changed the function of a room from a child's playroom into an arts and crafts room, because they didn't have any children at that time, and so it seemed reasonable to them. When the rest of the community came by and saw what had happened, many people were outraged. "What? If you can just change the function of a room just like that then I don't like sociocracy, because that's just too much power."

What had they not done the way we would have liked? They didn't ask for feedback. They didn't first say to the community, "We're thinking of doing this. We don't have kids. We could really use an arts and crafts school for us. And so this is something that we were seriously thinking about. What would to tell us?" If they had asked that question, they would have heard a pretty resounding response. "No, keep the kids room. We really want to be an intergenerational community. Having the kids room is our is our invitation ticket for people with children who are coming by and visiting and go, oh, look at this nice space. This is a welcoming space for families."

And in fact, they had to backtrack and reset the room to a children's room. And that community does have kids now. I don't know if that was why they have kids, but the lesson there was really: yes, you have responsibility and authority — you have authority to make decisions now because it's in your domain to change the function of the room — but with that authority comes the responsibility to get the appropriate feedback.

Ted Rau: So in summary, on this tension, our ideas to not run into the issues that we've described as to have a clear and agreed upon decision making system — to be clear about what does it mean to make a decision? Can one abstain? What happens if somebody disagrees? What if somebody objects out of those? And when is that moment? Do we just kind of shrug and say, I guess we've just decided? Or do we say, okay, here's how we make decisions and train everybody on using that system? And then the other one is integrate voices from outside the circle and integrate objections - that one of those things are skills that can be learned. It's not rocket science, it's just that we don't happen to learn it in school, although I think we should. So we still have to learn it after. But it's very doable. Next one.

What do we have? Oh, no, actually, it does have another one. And that is the thing that I referred to, is the processes that we use in sociocracy — and that I'm a big fan of — and that is if there is a proposal and it's now time to make a decision. When the person was reading the room, that's what I was missing, of just like, "What's the process here? How do how do we know we just got to a decision?" And so I can see how it goes as you allow for questions — maybe even in a round — you allow for reactions, probably in a round, which means everybody in that group, which would be small groups in sociocracy, would speak to the proposal, say what they think. And then we do a consent round. And if there's an objection, we know exactly what we do with that. I'm not going to go into it. That's going to be in the longer class. But if there's an objection, we know what we're doing and then we ultimately come back to consent again, probably with a better version of the proposal and ready to consent.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: Listening in meetings. You know, when we are in a meeting, we all have our opinions. We would like to be heard. If we're not heard, then tensions will rise. And so the more we can effectively listen to each other, the calmer we will all be together, and we can then take in and share the relevant information. And we need small groups for that, because when you have a group of 40 or 50, it's really hard to listen to everybody. You only listen to a few. So looking for that smaller group to be able to do the listening. And Ted, you want to share small groups story.

Ted Rau: Yeah, this is not necessarily even just a just a particular story. It's just all the many, many, many, many times in which — and I'm sure many of the people listening have had the same experience — of just the quality of listening is just completely different in a large group and in a small group. In a large group one can basically just hear some of the people, and it tends to be also the typical suspects that are comfortable raising their hand in a large group. And in smaller groups we can actually hear each other, and have a completely different sense of trust and belonging with each other. So I guess we're all for that. Go ahead.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: And having then a structure for the meetings is helpful. You know, the very basic meeting agenda where you check in as you arrive, so you share with each other how you are arriving at the meeting together. You get clear about, as you know, do we have everybody present who we need to have present, take care of the business aspects of the meeting, consent to the agenda, deal with your items of the agenda. Check out from the meeting and see how the meeting went for you. So having a really structured agenda process might seem like kind of rule bound to some, but it is what gives you the freedom to be present. It's like the rules of the game allow you to enjoy the game, so have really clear process that helps you enjoy your game. And a key aspect that we always do in such sociocratic meetings is the rounds. That's what keeps everyone's voice sacred. You know, everyone's voice matters when you do the round, you hear from everybody. If you do cross talk, then the informal power dynamics will rise. You know, the guy will speak over and over again in a bigger and bigger voice if people aren't agreeing with him, etc..

Ted Rau: There's another little addendum that I want to say here, and that is actually a story, and that is in our community we've been using sociocracy for, what, 12 years or so? And, you know, many people who had a hard time in the beginning are now happy in rounds, as far as I know. I know that for me it was quite something to get used to. I was completely new to it back then, and I remember struggling with rounds. But now that I've kind of gotten used to that kind of pace, it seems like the obvious thing to do.

However, I remember very distinctly because it shocked me a little bit, honestly, and a few years back we had a little somewhat informal. It was kind of a — I don't fully remember what it was — like a little task force that was trying to do something. It wasn't an official circle meeting. We didn't have a facilitator, we didn't have an agenda. We were just kind of talking about this one thing. And Jerry, this is actually a story that involves you. So there we were all happy talking, you know. Actually not all happy talking. It was four of us talking and Jerry not talking at all. And I have been kind of used to just talking when I feel like it. And even years of rounds have not really changed that, I can still go back into that mode. I guess that's what I'm saying.

So there was at some point then, Jerry said something that that I will never forget. He said, "Um...can we please do rounds? Because in the way we're talking right now, I would have to interrupt one of you to get a word in. And I don't want to have to interrupt you to speak." And that one really hit me because I was like, whoa. I was doing it, I was one of the people, although I know about rounds and I can teach about rounds, and yet if you don't have a practice of actually doing it and having it kind of as the agreed upon 'this is what we're doing right now,' it just slips away all of a sudden. So this is not about something that is kind of a personal, enlightening kind of thing. This is just a matter of practice and commitment. Do you do it or does it slip away and some voices might simply not get heard and you don't even notice it because in the heat of the moment, you don't notice it.

So that really brought home for me this awareness that the practice and the tools really matter. You cannot just cover those things with awareness. The awareness I had, and I still failed to act on it. So that's why I'm now putting more emphasis on the tools and the practice than just knowing that it would be a good idea. Otherwise, it's like doing exercise, like being athletic, because you don't get healthy by knowing that exercise is good for you, you know what I mean? You have to actually do it: that makes the difference. Anyway, whose turn is it?

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: I'll do the next one. I was just going to say, you know, Ted is an extrovert, I'm an introvert. In a formal context, when we do a round, and this is my space and I'm talking about things that I'm passionate about, I don't have any problem speaking. But go to an informal space, and that's when the story that Ted was talking about, in the informal space, if there are fast and loud talkers I may not speak. So then I need to find a way. It's like, "if I want to be part of this, I need to break in and say, you know, I want a turn." But that's kind of embarrassing. That's kind of lame. So if we all have that consciousness of inclusion, then there will be space.

Ted Rau: And you did speak up, right? I mean, you did eventually say it. Not everybody would. Many, many, many people would just walk away and roll their eyes and say all these stupid people that didn't even notice that I didn't speak. So I would have never heard about it. And that's quite shocking also. How many times does that happen? How many times? And I'm complicit in a process, contributing to a process, where that is happening and I never hear about it. So that's why I'm really, really big on tools.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: All right. Tension number four: conflict and engagement. You know, conflict happens. In our community we like to think that our Cherry Hill Cohousing is a fairly high functioning community. We have conflicts. We like to think that Sociocracy For All, you know, we're all highly trained and skilled. And, you know, we've been doing this for a while. We have conflicts. So conflicts happen. It's about knowing what to do with them as they arise, and doing what you can to do preventive work. But aside from that preventive work — which is all about everything we've been talking about so far — what do you do when they actually happen?

So two little stories here. One was, this is even before sociocracy in my own community, we would have a meeting. And pretty frequently John and I experienced tension between us. And I got into the habit of just saying to John as the meeting ended, "Hey, I'm going to go for a walk." So we would walk around this little loop around our community and talk about the meeting and how it went and what was going on between us so that we could clean the space between us, come back to center, come back to good connection between us, and see if we could get better at it for the next time.

The other story is pets. The whole issue of pets is one of the hardest ones in communities. We have to deal with outdoor cats, which is a very bloody mess, and we have to deal with dogs. So here was a situation where there were outdoor cats and somebody had a dog that barked whenever a cat sat on the banister in front of their house. And so they were so mad about that cat, the neighbor's cat, triggering their barking of their own dog that they started violating other policies to dealing with the pets, like going around without a leash with this dog that was a barker, and a very kind of energetic little dog. And so quite a few people were upset about the violations. And so what happened is that the circle that I was part of, we decided to send two people — trusted people, in a sense — who we knew had the respect of this particular family with the dog, and go to them and do what we called "eldering." Like saying, "Hey, this is what we're seeing. This is the impact it's having on the community. Can you please talk with us about what's going on for you? And let's see if we can figure out a way that you can honor the policies, because this is really painful for everybody."

And so we sent that delegation of the two of us to talk to that couple. We had the conversation. They could hear it without the shame and blame kind of place, it wasn't a public shaming, it was a private meeting. And we could talk through that and acknowledged, "Yeah, I get it that it's really frustrating, that the cat sits there and triggers the dog barking. And that's not enough for you to go and retaliate and do revenge violation." And so they heard that and then they stopped. It really changed their behavior.

So all our ideas, this connection before corrections, instead of just telling them that they're wrong and bad, go talk to them, listen to what they have to say, understand their concerns, validate their concerns, and then also still restate what you see as important from your perspective that you want to have heard.

The other idea which we have in our community, we formed a care and counsel circle, and they have produced a whole little pamphlet of different ways to deal with conflict. So you can, and different people in the community who are able to respond to those. So there's a number of people who can do nonviolent communication so you can invite them to help you out with listening frame using nonviolent communication. There's other people who know Byron Katie's The Work and you can invite them to help you with that. There's others who know Thích Nhất Hạnh's listening process, and you can invite that process. There's people who know meditation and mediation. So we've got a set of options that we offer to people that they could make use of. And they do. I see a question, "What happened to that cat and dog?" And maybe we'll tell that story in the question and answer period, because it's a longer story.

Ted Rau: All right. Let me just see. Okay.

So this has already come up a little bit, but I think it's a really key issue also that it deserves its own points. So in this way of having small circles making decisions in their domains, now we have small groups getting input, but then making decisions on those issues. And that now means that they are now 12 committees or circles making decisions. So, we need to get good at really making sure that all the information flows, because each of those 12 circles makes decisions that affect me as a community member. So there's not just one place where one can hear things from, but 12 different places. So there is this dance between the community and the circles that really needs to be done well.

So circles need to be good at reporting out and also getting feedback. And that basically becomes a forever loop of: we hear how this policy is being received, or how people are accountable to it or not, how it's working, how it could be improved; and the community hears what we do, and what we do with the feedback that we've received. So that just always goes back and forth, just like in that story with the kids room that was converted into a different room. That loop was missing, right? So that was part of the issue then.

And a similar story, just a little bit different, and its nature is we- the common house circle in our community, which we're not a part of, changed the policy so that grown-up children who used to live here but now are grown-ups and live somewhere completely different can't just walk into the exercise room and use it. And there were reasons for that. But somebody was not reading Common House Circle emails and his daughter or son went there, and somebody kind of pointed that out. And the parent of that adult child was really sad and shocked, but then had to see later that there were several pieces of information that the circle had really tried hard to get feedback and let people know, and so on. So there's this mutual responsibility, right? The circle can only do so much. We also really have to pay attention.

And so I guess the circle needs to say it more than once and in more than one way if it's important. And yet there is this mutual responsibility. So we meet each other with the information. So that's something that just is an ongoing thing to get the design going. So that really works. The bunch of things, tech solutions that of course that one might have for that and also just practices and habits to to harvest information, or transparent minutes, or other minutes of all circles are open to everybody in the community. And we make sure that that is the case. Because if a circle makes a decision and I read about it and go like, "What? You decided what?" I want to be able to read back of how did they get to that decision? Because most likely once I know more, it actually makes sense to me. Or at least I might have respect for the decision that was made. Typically people aren't total idiots, right? So typically the more you know, the more you understand.

So then, for example, in plenaries there might be places to share little things of, "Hey, here's what happened," so that people are informed. So all of that is part of the picture, the information flow, of things running well. And that's actually my closing comment here. And another little story, actually to enter into that. Sometimes we have people that are like, "Oh, can we visit A sociocratic community? I call them so sociocracy tourists. They exist. They existed more before the pandemic, but they do still exist. And so then they want to attend a coordinating circle meeting and see what that's like. And I typically warn them and say, you know, it's not all that interesting. Because, I don't quite know what they expect, but I can tell them what they will see, and that is basically just normal process like that.

Good governance is basically silent, right? Good governance is such that you hardly even notice it. So all the processes around rounds, about consent and clarifying questions, and this and that, once it's going, it's just something that you do. It's not so much that you notice that there's this whole other layer of magic process. It just looks like normal people talking to each other and everybody having a certain way of doing it and being clear about what we're talking about. And that is typically news to people, that it's more the absence that they will notice: the absence of drama, the absence of being interrupted, all of those things. So good governance is simply smooth in silence. That's what what I'm striving for. Because if it's smooth and silent, then we can just focus on what we want to do with each other instead of having to focus on all the drama between us. So then we can be paying attention to what we're interested in our community life and in each other's stories. And that's afterall why we want to be in community, typically not because of the drama. So there we are. Unless you have another closing commentary, or we look at the questions.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: And there was a question about what happened with the cat and dog story.

Ted Rau: Tell your cat and dog story.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: So one aspect is in that conversation between the two of us who are talking to that couple, as we heard their concerns we could then strategize about what would be helpful here. So in the short term, it was "okay, pull curtains down so that the dog doesn't see the cat." And the other practical idea was to get a water spray and just keep spraying the cat, when the cat comes into that spot, so the cat starts learning this is not a very pleasant spot to hang out in. So those are the short term answers that we could creatively think about once we were in conversation rather than in blame space.

The longer story is that there were a lot of outdoor cats in our community and there was a lot of blame and anger about that because the cats were pooping in sandboxes, the cats were killing the birds that people were planting bushes and trees to attract. So there was tension because there were also cat lovers who were, you know, "cats belong outside, that's their natural way of being." So there wasn't any way to resolve that. And matter of fact, we had a policy which had a moratorium on new outdoor cats for a while, and then that moratorium ended and there were no rules anymore, again, because nobody had a sense of how to approach it. So that was one of the first topics that we dealt with when we adopted sociocracy we went right at the outdoor cat policy.

And it involved talking to people, the people who loved the dog, the cats, the people who loved the birds, the people, the parents of the children. So interviews, surveys, coming up with a proposed policy, getting feedback and making a decision, and even having to perhaps change it a little bit. And what I like to say is that what we came up with was a policy that most people did not like. Because most people were either for or against. But it was a policy that everyone could live with, could work with, because it did limit the number of outdoor cats, but it didn't completely rule them out. And the decision process that we used, because we did so much feedback gathering that we earned the trust of the community in the process of making the decision. And we haven't heard an issue about outdoor cats since, and that's been nine years or so now.

Ted Rau: Which speaks to that point that good governance is silent, right? It's one of those things. So it's the absence of drama around pets that is showing how well it's working on that end.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: Yeah, there's another story which I won't tell now, but ultimately there's another bit of story around dogs. You know, something happened with a dog jumping on people, and so we had to come up with a process to deal with that. And, now having a process that we had to develop, because it was a new experience for us, now we've got a process and we haven't heard the issues on that front for a while. You know, good governance.

Ted Rau: So thank you. I see two questions in the Q&A, right. I also see things in the chat. So that is a little confusing. Wait, wait, wait. Let me read it. What's the minimum number of people in order to implement sociocracy? Oh, I want that one. I'll answer it. So I'll take the one from the chat. And then Jerry, you can look at the ones in the Q&A. And so this question is about would it make sense to learn sociocracy if there's only five of us in a small community? Yes, because this happens to be a pet peeve of mine. I'll explain. Because it is so common that community started out without a governance system that is explicit. And then, by default, those five people probably come together and somehow figure out that probably they basically agree on something and then they assume that the decision, and that informal way might work for five people.

But then what happens if now you add another five, and another five, now you have 15 people. Now we have that situation. But you don't hear some of the voices anymore. Let's say you still let it slide and you add another five, and another five. Now you have 25 people. And for sure, there are voices that you don't hear anymore if you meet in a group of 25 people. Now, typically what happens is that people then start to notice, oh, we probably need some process here, we probably need some structure. And then typically, it doesn't take long until there's conflict. And then you have the situation that people now say, "oh, we need structure, we need a governance system." And then some people look at governance. But by that time, sadly, sometimes what happens is that there are already factions and people are already burned on this person or that person, and some lack of trust has started to take root.

And in that situation, it's really hard to introduce the governance system because now you can have that effect of like, "well, if you want that governance then it can't be good, because you're a jerk," right? Because he did this and that, and this and that, two months ago. So now all of a sudden there's already all these stories. So it becomes harder and harder to adopt a governance system later on because of the lack of trust and just because of group size. So do it early. Do it as early as basically the very first moment. You are an organization and as a group of five with a vision, you are an organization. And one other thing, because I know that's such a common question that people say, Wait, but how can the five of us decide what the governance system will be for the community? The way I see it, your governance system, just like the vision is part of the invitation. So you probably want that set. And on the basis of that, you're inviting in people.

The other pieces you can set the basic principles in place and then review it so you're not making a decision of one particular way of doing things, because there are variations even within sociocracy, and you're not making a decision on everything till the end of time. So make a decision for the next year. Next year it might be ten people: review it. But that way you'll always have a system so that you don't have a situation where you don't have a system, and you don't know how to create a system, because then you've locked yourself out of your own thing.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: Ted wrote a book about this called Who Decides Who Decides? And it's like, okay, first of all, be clear what your invitation is, what you want to include. You know, are you a vegetarian community, or are you a omnivorous community, are you're going to be south or north of the city; all the core elements of what your invitation is. Second, know who your founders are. You know, who is the initial group of people who are going to start making decisions. And three, know how you're going to make decisions. Once you've got those three things in place. Now you can grow and change. If you don't have those three things in place, you're liable to get into lots of arguments about, "No, I want this," "but no, I want that." "no, we should decide it this way," "no, we should decide it that way," "no, you don't have authority." You just open yourself up. Again, as I was saying before, you're now playing a game without having agreements about how you're going to play the game. And it's not that much fun.

Ted Rau: And it's a little bit like a group of nine year olds that play different rules for the game of Uno. And half of the time they play, half of the time they argue about the rules. That's no fun. Jerry, did you have a chance to look at...

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: These questions in the chat? One of them was how are circle members initially chosen or elected. So it does vary according to what stage of development your community's in. Because as the story that Ted was just responding to is a small founding group. Okay, you choose each other and say, "are we the five of us willing to be the founding group? We are. Great. We're going." And now that group of five from then on selects anybody else who joins the group.

Every every group in A sociocratic organization has a choice about who its members are. So whether you have one founding group of five, or you've got ten different committees going on, each one of those has a choice about who its members are. So you cannot impose yourself on a group without the group saying, "okay, we want you here." So it's a mutual choice. The other thing is if you've got an organization that's already in existence, then how you do it? What's that transition from the way you were doing it before to the new way? And different groups have done it differently. Some groups have been very conscientious and had every single person chosen for every single group. Most groups that I know have been much more, you know, "where do you want to fit in" and "let's let self-selection happen" into the formation of the initial groups. The way we started in our community, when we adopted sociocracy, we had everybody stand in groups and say, okay, these people want to be the Buildings and Grounds, these people want to be the Membership Circle, You know, are we okay with that? People just say, Sure, that's okay. Then we as a whole collective group nominated the leaders for each of those circles. And then we had each of those circles do a fishbowl and among themselves do the second part of selecting who they wanted to have as their leader or their coordinator for that group. And that's how the whole community had some input. But those who were going to work together made the final decision about who their coordinator was going to be. And I can say, Will, if you take the class, we'll talk more about selection process and will demonstrate that whole process with you.

The second question in the chat was the relationship between vision, values, and potential conflict. And I'll say something. And I'm curious what Ted might say on this, because for me, this is a guiding principle. The values might be a guiding principle, but what's most important is the commitment to give each other feedback, the commitment to join together in a dialog. You know, are we committed to engaging with the conflict that we might have and learning from that? I've seen organizations that have beautiful sets of visions and values, but their practice is not very good. So to me it's what is your practice of engagement? You have a way of doing it that people have a sense of trust in, it's part of the invitation, that people have said, "Yes, I'm willing to. I know that I'm going to be self responsible for doing the best I can with processing conflicts that happen among us." Ted, do you want to answer more? Vision, value.

Ted Rau: I just...no. Also in the interest of time actually. Now if it's okay I'll jump to the second to last question, and then we probably do have to stop, right?

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: Yes.

Ted Rau: And now there's a new question that I don't think we'll have time for. But rounds in the plenary: so, yes, as you have heard from us several times, sociocracy is built on small groups and everything can be done in small groups. So there is a plenary in our community, a plenary meeting about once a month, and that is typically for connection, for feedback, for just getting to know each other, for giving a circle feedback about something, hearing what circles are up to. So there's a whole different function. It's typically not a decision making meeting. I can put something in the chat where I'm describing how the processes from social policy can be used for plenaries. But just always keep in mind that's not what it was originally intended to do because of the quality of listening and deliberation that it's just so much, so much better in in small groups. So it is kind of using it for a different context than it was intended for.

Jerry Koch-Gonzalez: I think the last question requires a more complex answer. It's not actually a question it's a statement at this point. A board makes decisions and sociocracy is more about the operational day-to-day management. And yeah, it doesn't have to be that separated. And there are ways to deal with that. But I think we don't have time to respond if we're going to the closing. And I do need to hop off because I've got another meeting shortly after the end of this.

Ted Rau: Lauren:, over to you.

Lauren: Awesome. Well, thank you, guys. It's so great to have you join us again and to share all of your wisdom with us. Thank you very much for joining us. And I'm very much looking forward to hosting you two again for the Sociocracy For Communities course that starts in a few weeks. I did put a link to that in the chat with some more information about the earlybird discount and where you can learn more. Also very grateful for you all for joining us today. I do hope that you got some helpful information from the session and we do hope to see all of you again, if not in the course, in another online event. So that is all we have for you. So thank you all Again, please enjoy your day and we hope to see you all again soon. Take care.

This transcript has been lightly edited for readability.

Add new comment