Walking the Feedback Talk

cross-posted from Laird's Commentary on Community and Consensus

As a professional facilitator for more than three decades, I've had ample opportunity to observe which skills make the most difference. As a facilitation trainer the past 15 years, I've collected plenty of data about which lessons have been the most challenging for students to digest.

Taken all together, I've decided to assemble a series of blog posts on the facilitation skills I consider to be both the hardest to master and the most potent for producing productive meetings. They will all bear the header Key Facilitation Skills and it's a distillation of where I believe the heavy lifting is done.

Here are the headlines of what I'll cover in this series:

I. Riding Two Horses: Content and Energy

II. Working Constructively with Emotions

III. Managing the Obstreperous

IV. Developing Range: Holding the Reins Only as Tightly as the Horses Require

V. Semipermeable Membranes: Welcoming Passion While Limiting Aggression

VI. Creating Durable Containers for Hard Conversations

VII. Walking the Feedback Talk

VIII. Sis Boom Bang

IX. Projecting Curiosity in the Presence of Disagreement

X. Distinguishing Weird (But Benign) from Seductive (Yet Dangerous)

XI. Eliciting Proposals that Sing

XII. Becoming Multi-tongued

XIII. Not Leaving Product on the Table

XIV. Sequencing Issues Productively

XV. Trusting the Force

Walking the Feedback Talk

For the most part, contemporary culture is downright awful at giving and receiving feedback. This shortcoming is a major impediment to clear communication in all settings, and undercuts the quality of relationships everywhere. In short, it's a big deal.

In cooperative culture the stakes are even higher, because the lives of participants are more interwoven and there is more opportunity to rub each other the wrong way. One of the main challenges to creating robust communities is figuring this out—both on the group level and the personal plane. The dynamic is complicated by the fact that groups rarely make this explicit up front (if ever) and people often join (buy a house) without understanding that their satisfaction—and that of those around them—is dependent on the group's ability to foster and sustain clean feedback among members.

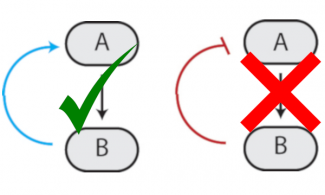

In the effort to develop the group's capacity to work well with feedback, facilitators can play a pivotal role in modeling how to accomplish this with grace and minimal reactivity. (You can't very well ask it of others if you are not able to do it yourself.)

On the giving end, many consider it rude to speak critically of others—at least to their face. Where that's the norm, people try to swallow their irritations (a practice that leads to heartburn), or manage them through pillow talk (venting with their partner) or parking lot gossip, which is a virtual acid drip on the social fabric of the group. Not only does the would-be recipient miss out on the information, but it's hard on the giver who withholds.

Going the other way, it's also hard for people to receive criticism. It can be embarrassing, or even humiliating. Some will automatically translate critical comments into shame. Many are susceptible to conflating criticism of actions with criticism of the person. Strong negative reactions can lead to shut down, exit, and damaged relationships. If hearing criticism is unpleasant enough, people will learn defensive behaviors to deflect it or otherwise discourage others from giving feedback. It can really gum up the works.

Trump, for example, offers a textbook example of how to deflect criticism through aggression. Invariably, his response is to lash back, often upping the ante by pushing the nastiness needle into the red. In doing so, he's sending multiple messages:

—Think twice about criticizing me, because you'll immediately get double your ugliness back. In fact, I may publicly ridicule you for having the audacity to speak out.

—I consider people who criticize me publicly to be enemies. I demand loyalty from my friends and allies, and it's disloyal to be speak critically of anything I say or do.

—Criticizing me will not change my behavior. If anything, I'm likely to do it more.

To put it mildly, his response is uncooperative, and does not encourage people to express reservations and concerns (what good does it do, and who needs the grief?). It's a highly dysfunctional management style, and destructive of group cohesion and camaraderie.

To be clear, I'm not saying that you can't have reactions to criticism, nor am I suggesting that there's anything wrong with you if you do. Reactions are normal part of being human and you may have trouble with either the content or the delivery, or both. That said, a reaction does not dictate a response. You always have choices about how you respond, and I'm suggesting that you hold onto that possibility like a life ring in a storm-tossed sea. It will ultimately serve you best, I believe, if you respond in a way that most honors relationship—which is the lifeblood of cooperative groups. Instead of blood letting; think blood flowing.

How do you do that?

• Start by acknowledging what you heard, paying particular homage to the impact that your words or actions had on the other person, as they reported it. This is a good idea even if you don't like what the person said or feel you've been misunderstood. (Lashing back may feel good in the moment, but it's almost never productive.) The point of this is twofold: a) it establishes whether you heard correctly; and b) it values the other person's experience; it shows that you care, which is deescalating.

• If you have a nontrivial reaction to the feedback (let's be honest; sometimes it hurts!), it may be a good idea to delay a response until you're past the rawness. There is a world of difference between reporting a reaction and being in the reaction. If you're in high dudgeon, you might want to wait until you're no longer a drama queen. Why? Because the bottom line is connection and communication; not "winning" or proving that you have the inside track on reality.

The biological equivalent of criticism is pain—it's a feedback loop that's an essential part of health management. If you step on a nail it's a damn good thing that your foot hurts—alerting you to take a gander at your hoof. If you touch a hot pan on the stove, pain immediately tells you to pull your finger away, before you do serious damage. I'm not saying you should enjoy pain; I'm saying you should be thankful that you know when you're damaging your foot or finger, so that you can deal with it promptly. If you were insulated from pain (a health risk for diabetics) you might walk around with a nail in your foot, or seriously burned fingers and that would not be good.

Similarly, it's not good if your actions or words have triggered pain in others and you are not aware of that impact. While you may need to exercise discernment about what to do with that information—and it may or may not result in a shift in your behavior—if you don't get the memo, then you don't get the opportunity to take it into account. And it is never in your interest to not have the information—so long as it's genuine.

What all this adds up to is that facilitators need to do sufficient personal work to keep their own feedback channels open (flawed models are not that inspirational). What's more, at least some of the time criticism will be directed your way in highly public settings, and occasionally delivered raw (by which I mean with little or no care given to how it will land). While this is undoubtedly unpleasant and may not be fair, it goes with the territory, and can go a long way toward leading the group into the culture it needs.

Go to the GEO front page

I’ve lived in intentional community for 41 years: 39 years at Sandhill Farm (a small, income-sharing community I helped found in 1974 in northeast Missouri), followed by 20 months at nearby Dancing Rabbit, an ecovillage started in 1997 with a core mission of modeling how to live a great life on a resource budget that’s only 10% of the US average. Today I live in Chapel Hill NC, where I’m trying to pioneer a new community with close friends. For the last 28 years I’ve also been integrally involved with the Fellowship for Intentional Community—a North American network dedicated to providing the information and inspiration of cooperative living to the widest possible audience. Recognizing the value of what is being learned in intentional communities about how to solve problems collaboratively and work constructively with conflict, I started a part-time career as a process consultant in 1987. Today, I’m on the road half the time conducting trainings, working with groups, and attending events all over the country. Recreationally, my passions include celebration cooking, duplicate bridge, wilderness canoeing, and the New York Times Sunday crossword.

I’ve lived in intentional community for 41 years: 39 years at Sandhill Farm (a small, income-sharing community I helped found in 1974 in northeast Missouri), followed by 20 months at nearby Dancing Rabbit, an ecovillage started in 1997 with a core mission of modeling how to live a great life on a resource budget that’s only 10% of the US average. Today I live in Chapel Hill NC, where I’m trying to pioneer a new community with close friends. For the last 28 years I’ve also been integrally involved with the Fellowship for Intentional Community—a North American network dedicated to providing the information and inspiration of cooperative living to the widest possible audience. Recognizing the value of what is being learned in intentional communities about how to solve problems collaboratively and work constructively with conflict, I started a part-time career as a process consultant in 1987. Today, I’m on the road half the time conducting trainings, working with groups, and attending events all over the country. Recreationally, my passions include celebration cooking, duplicate bridge, wilderness canoeing, and the New York Times Sunday crossword.

Add new comment