Permaculture Meets Cooperation at OrganaGardens

¿Qué aprendió el árbol de la tierra

para conversar con el cielo?

(What did the tree learn from the earth

so that it could talk with the sky?)– Pablo Neruda, Libro de las Preguntas, XLI

OrganaGardens Cooperative1 , a landscaping business in Colorado’s Pikes Peak region offers an inspiring example of how to nurture and structure a cooperative culture that takes into account not just collective ownership and shared resources but mutual care and social transformation. Founded as an LLC in 2000, the self-described “collective of organic gardeners and garden designers, experienced landscapers, and permaculture designers” is now in the process of converting to a cooperative under Colorado State.

Before Covid-19, most of the discussion about cooperative conversions focused on the “silver tsunami” of retiring small business owners seeking to exit their business without closing it down or selling out to a larger corporation. The pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis has added the challenge of keeping small businesses afloat and creating economic opportunity in the face of collapsing demand, rising debt, job losses and rising competitive pressure. At the same time, the upsurge in mutual aid efforts has added urgency to the search for alternative ways of doing business. There are many resources available to help owners and workers make sense of the options, especially when it comes to legal and organizational questions.2 But to make the cultural transition to cooperation, we need also creative examples: people who are finding new ways to cultivate and grow cooperatives, not just in the narrow sense of isolated businesses, but as elements of an emerging system of justice and regeneration.

OrganaGardens was founded by Becky Elder, a leading permaculture practitioner and educator who had already been working in collaboration with like-minded gardeners and landscapers in her businesses “Blue Planet Earthscapes” and “Becky, the Gardener LLC.” A co-founder of Pikes Peak Permaculture, Elder is a long-time environmental activist in organizations like Ancient Forest Rescue, SINUAPU (wolf recovery), and Earth First!. Elder has been active in local politics and in alternative economic projects like Transition Town Manitou Springs where she began collaborating with Brian Scott Fritz, OrganaGardens’ current business manager.

In its first incarnation, OrganaGardens operated as a kind of loose – but very effective – coalition. Demand for their work grew and OrganaGardens thrived. So much so that by the end of the third year Elder’s accountant at the time became nervous, worried that “the increasing growth in sales income and the unusual structure/relationship that the coalition fostered among its members might attract the attention of the IRS.” They decided “to end the coalition and return to a more conventional model of doing business.” OrganaGardens started operating as a traditional LLC. But the urge to collaborate remained and in 2018, Elder and Fritz began talking with other landscapers and gardeners about converting OrganaGardens into a legally recognized cooperative.

The conversion process started in earnest a year later, with support from co-op development specialists Dan Hobbs and the late Bill Stevenson from the Rocky Mountain Farmers Union. OrganaGardens was preserved as the “parent” company, with each of the eleven co-op members creating their own independent gardening companies operating as sub-contractors.3

Landscaping and gardening are largely seasonal work; in the busy spring and summer months demand can quickly outstrip capacity. To meet the demand, OrganaGardens members decided to hire non-member workers on a short-term basis. The workers are hired at $15 per hour for no more than a total of 39 hours. This ensures that most work is done by co-op members and provides aspiring members the opportunity to work with the cooperative on a trial basis. If the cooperative members and the new worker feel it is a good fit, they can join the cooperative.

Why a Cooperative?

Cooperation, equality, mutual care, and learning had been part of Elder’s practice all along, in keeping with the larger ethos of permaculture. As a cooperative, she says, OrganaGardens can be “a voice in the world both as an individual (one member, one vote) and also as the whole of OrganaGardens moves into philanthropy to further the permaculture ethics... ” The cooperative form appealed to her for a number of other reasons:

-

it seemed easier to manage than a traditional business;

-

it offered the “added value of shared collective brilliance, knowledge, and the skills of members being shared willingly for the benefit of the whole and the future” as well as shared tools and resources;

-

it seemed suited to building the capacity of the young people who constitute most of its members “to operate as professional landscapers while developing skills and expanding their knowledge;”

-

it offered a way to support and encourage members to “step forward and participate in social movements, to participate in the larger "rooms" of the social works of this country;”

-

the group can provide “support and compassion to the individual as life happens (to us all!)”, and

-

it held the promise of sustainability, “OG outliving all of us into the future is a wonderful vision.”

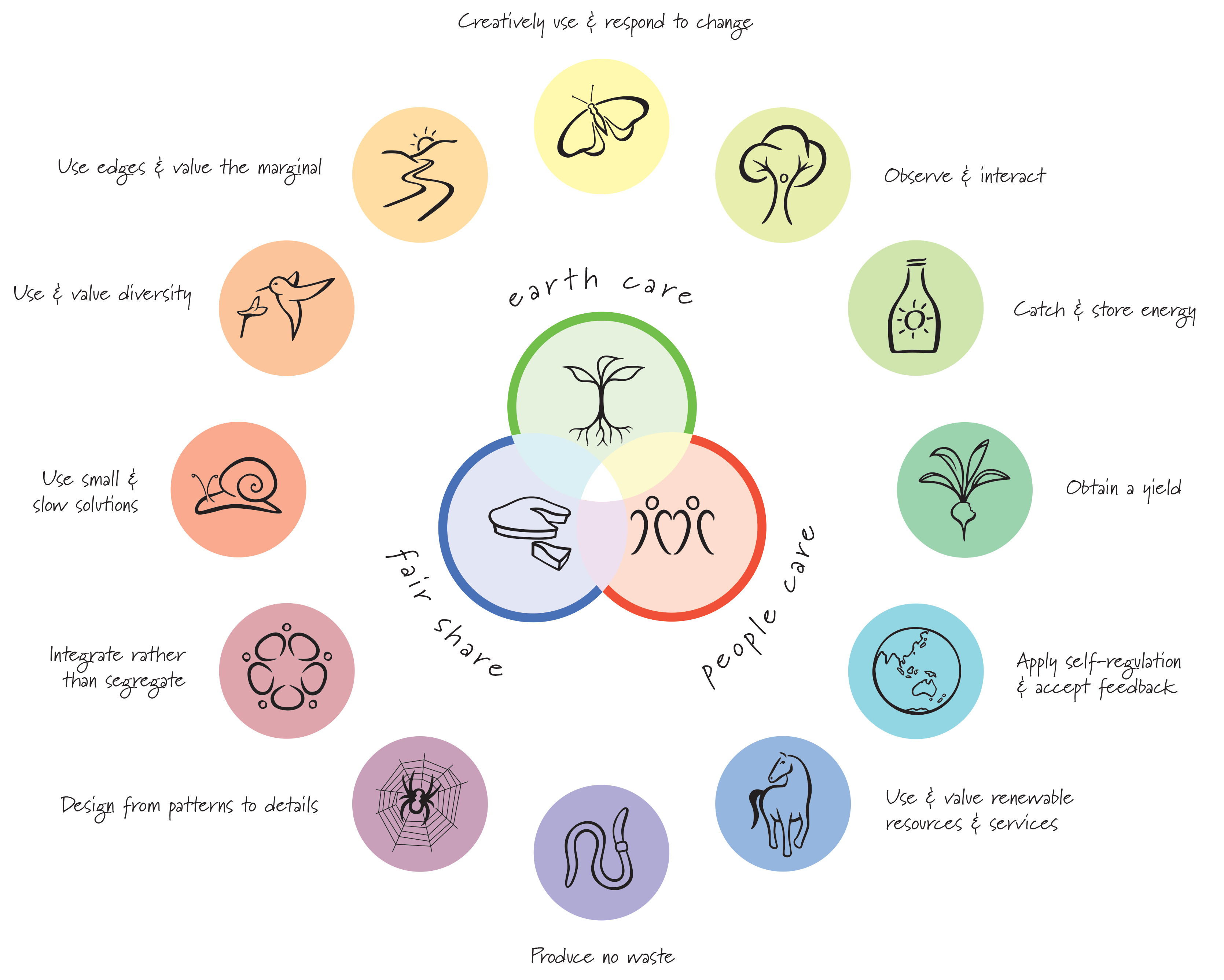

In short, cooperative organization was a good fit for a group with a clear and effective business idea and a common vision of shared resources, personal and collective growth, constant learning, and social transformation, offering a way to put into business practice the permaculture principles of care for the earth, care for people, and sharing of resources.

- Becky Elder

An Innovative Point System

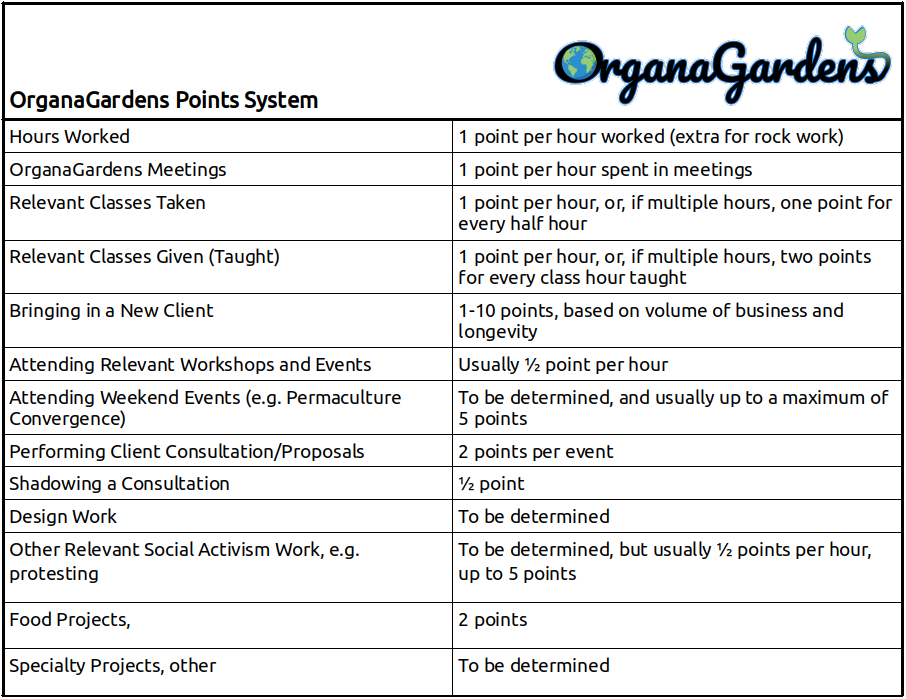

One challenge for cooperatives is how to ensure that the group’s commitment to social transformation stays at the center of their practice. For OrganaGardens this means permaculture as well as cooperative principles. To that end they established a point system for remunerating various types of work, including livelihood work, but also care work, education, and activism.

In a cooperative, the money used to compensate members for their labor comes out of the surplus generated by the enterprise.4 Some of the surplus may be used for buying new tools or equipment, some for creating a reserve fund, some may be donated to other organizations or projects. At OrganaGardens, the group decided to compensate members not just for the work they do for a living – designing, landscaping, and gardening – but also for pro bono and care work inside and outside of the cooperative.

Members accumulate points throughout the calendar year, based on a point system approved by the members. According to Fritz, the process is “all very spontaneous...”

“when members fill in their time sheets, they often put down activities like tabling at the farmers market, sitting on organizational boards, attending protests, taking or teaching a particular class, etc. and the number of points that each activity may represent. I double check this when I receive them.”

At the end of the year, assuming the cooperative has a surplus, they determine how much to retain to continue to pay company expenses, including taxes, operating expenses for the following year, reserves, etc. The remaining surplus is distributed to members according to their accumulated points. “So far, we have done this only once, in 2019, and it seemed to work fine,” says Fritz. “Members received anywhere from $165 to $2870. This dollar range represented a percentage of income range of 19% to 31% of yearly income.” Points are credited according to the following system which, Fritz points out, is always open to revision.

[Correction: rock work does not earn extra points. -MN]

For Mercedes Perez-Whitman, a 26 year old landscaper, owner of MycoSprings, and founding member of OrganaGardens, the cooperative has offered the chance to operate within a non-hierarchical structure.

“I have been able to voice concerns and feel heard… I have worked in places where I didn’t feel comfortable to speak up or if I did my concerns weren’t taken seriously.” She also embraces the points system. “I love it, it really helped my dividend last year. I do a lot of volunteering, going to different conferences or gatherings. I lead workshops, go to meetings, for example for the Pikes Peak Mycological Society. I go to Colorado Springs Utilities board meetings [about closing down the coal power plant]. While I would do this advocacy and education anyway it’s great that I am rewarded for it… It is also beneficial for the cooperative since we are able to bring more awareness to OrganaGardens. We table at the Colorado Farm and Art Market, giving away plants to people who donate to local activist groups like the Empowerment Solidarity Network and the Haseya Advocate Program.”

Conclusion – Towards a Cooperative Permaculture

“As a socially conscious organization, OrganaGardens Cooperative follows the deep ecology ethics of earth care, people care and sharing the surplus. Therefore, we actively take a stand around food sovereignty and food justice (the principle that all people inherently deserve affordable, healthy and fresh food and water.) We recognize and champion ancient and modern earthwork, gardening and farming technologies in our work, which support the principle of authentic sustainability and community resilience.” (from the OrganaGardens website)

Cooperative developers will sometimes stress that cooperatives operate to benefit their members, distinguishing co-ops from traditional for-profit businesses which operate to benefit their shareholders. But that’s a bit like saying a garden exists to benefit its gardeners. It’s true, but misses the point. There is a world to be gained – and protected – when we understand our work and ourselves as part of a larger social-ecosystem. The worldview, values, and core practices of permaculture provide uniquely fertile ground for developing regenerative cooperative models of work and ownership that respond to our increasingly unstable environmental and social context.

- 1https://organagardens.com

- 2See for example the Cooperative Educators Network https://ed.coop/learning-path/worker-co-op-conversions/; the Co-op Law website https://www.co-oplaw.org/legal-guide-cooperative-conversions/; and the Democracy at Work Institute – https://institute.coop/resources/lending-opportunity-generation-faqs-and-case-studies-investing-businesses-converting

- 3A local artists cooperative – Commonwheel – uses a similar structure. https://www.commonwheel.com/

- 4See Luis Razeto Migliaro, “How to Create a Solidarity Enterprise,” Unit VII (forthcoming on GEO.Coop)

Citations

Matt Noyes (2020). Learning from the Earth: Permaculture Meets Cooperation at OrganaGardens. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/learning-earth

Add new comment