Kichwa Artisans and Farmers Create Economic Alternatives in the Amazon

[Editor's note: we at GEO wish to extend our deepest condolences to the people of Ecuador who recently experienced a devastating earthquake that claimed the lives of hundreds of people. The following article from our archives (originally published in 2004) recounts the beginnings of the Kallari Cooperative, a co-op composed of Kichwa farmers and artisans in the Ecuadorian Amazon. From their start as a small handcraft cooperative, as detailed by Fernandes below, Kallari has grown into a successful bean-to-bar chocolate producer and exporter whose products are found in many US grocery stores and food co-ops. You can find out more about Kallari on their website (be sure to watch the video). We wish the worker-owners of Kallari and the people of Ecuador all the best in their recovery.]

A Class that Changed My Life

In June 2000, I was a teaching assistant in a three-week course in Culture and the Tropical Rainforest for my advisor Dr. Pamela Erickson at the University of Connecticut. I could not have known when I agreed to help teach this class how much the course of my life and my perspective of the world would change forever. We brought six students to the Jatun Sacha Foundation's Biological Station, located east of Tena, Ecuador in one of the world's most biologically rich regions. The Foundation offers students and researchers the opportunity to learn about the Amazon Basin region of Ecuador's rainforest. Not only was the natural environment breathtaking, but the people who lived in this region and the others who worked for Jatun Sacha were some of the most dedicated people I've ever known.

In June 2000, I was a teaching assistant in a three-week course in Culture and the Tropical Rainforest for my advisor Dr. Pamela Erickson at the University of Connecticut. I could not have known when I agreed to help teach this class how much the course of my life and my perspective of the world would change forever. We brought six students to the Jatun Sacha Foundation's Biological Station, located east of Tena, Ecuador in one of the world's most biologically rich regions. The Foundation offers students and researchers the opportunity to learn about the Amazon Basin region of Ecuador's rainforest. Not only was the natural environment breathtaking, but the people who lived in this region and the others who worked for Jatun Sacha were some of the most dedicated people I've ever known.

One person, in particular, who became a good friend is Judy Logback, a Kansas native who holds a degree in Biology and Spanish from Beloit College in Wisconsin. Since graduation five years ago, she has worked with the Foundation and lived with the surrounding Kichwa communities, focusing on biological conservation. Throughout her first year in the Amazon, she realized that the people living along the Napo River were struggling to meet their basic needs and were often forced to log for intermediaries or work for the oil companies. Looking for ways to assist the people earn a living without long-term damage to the forest became her main priority. It had become more important than ever to find economic alternatives—ones which could promote both a healthy forest and healthy communities. As one community president put it:

I don't know why we worked so hard, like ants, taking out lumber. Cutting the wood and transporting it requires hard work and long days, in the mud, carrying out the wood and getting so dirty, walking out several kilometers to the river. We took it out and then floated it down the river to the port, sold the planks for almost nothing, when we could have sat in the house making crafts where we don't have to get wet or dirty. It is not worth it, selling wood or working for the oil companies. That is really hard work, and making crafts is very good.

~Pedro Cerda, President, Communa Shinchi Runa, February 2000.

A Grassroots Alternative that Respects the Forest

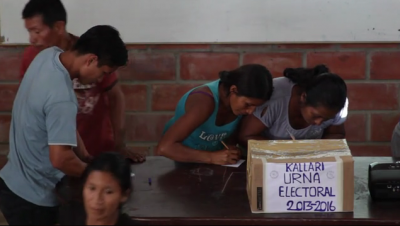

It was in this context that Judy, along with some innovative Kichwa people, created the Kallari Handcraft Cooperative. Started in 1998, this cooperative is a grassroots organization, dedicated to providing economic alternatives congruent with traditional philosophies, which do not degrade the forest. The project has grown to include some 700 Kichwa artisans who have developed numerous natural rainforest products for international sales. They make necklaces, bracelets, woven bags or shigras, baskets, and wooden bowls. The project is staffed with Kichwa people and directed by Logback. The Kichwa found that they could generate supplemental income by creating non-timber forest products to sell overseas. The key lies in informing the public through an international promotion campaign. Kallari delivers a message of concern and shared global responsibility for preserving one of the most biologically diverse regions on the planet.

The Kichwa have traditionally made products from rainforest materials, but they needed the assistance of an outsider who was willing to test niche markets, export goods for higher profit, and to move the products from the jungle to the retailers. Judy took on this enormous task with fervor and over the past five years has maintained a marketing system and an infrastructure in an uncooperative country. Roads to the Amazon wash out constantly, unexpected snowstorms in the mountains halt traffic for days on end, bags of crafts are stolen on public transportation, and the Napo River crests during the year-round wet season, making crossing the river impossible.

The Kichwa have traditionally made products from rainforest materials, but they needed the assistance of an outsider who was willing to test niche markets, export goods for higher profit, and to move the products from the jungle to the retailers. Judy took on this enormous task with fervor and over the past five years has maintained a marketing system and an infrastructure in an uncooperative country. Roads to the Amazon wash out constantly, unexpected snowstorms in the mountains halt traffic for days on end, bags of crafts are stolen on public transportation, and the Napo River crests during the year-round wet season, making crossing the river impossible.

Despite all of the obstacles, Judy and the Kichwa artisans have met with great success. Within five years of existence, the Kallari project has brought nearly $100,000 to the Upper Napo River region. Some of the profits are used to develop programs for education and healthcare. The Jatun Sacha Foundation works to ensure that only renewable resources are used in the manufacture of Kallari Cooperative products. It can take up to six cleared fields to harvest one crop of cocoa; much smaller spaces are needed to gather material for necklaces. For example, people grow plants for crafting such as pita in the shade, along the edges of their charkas or manioc gardens. ( Note: Pita is a durable fiber plant and an invaluable resource for indigenous people living in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Pita fibers are the principle raw material used in fishing nets, woven bags or shigras, hammocks, and traditional regalia.)

The Culture and Situation of the Kichwa

Crafts that are handmade by Kichwa artisans are marketed with educational brochures, which bring to life the complicated situation in the Amazon region. Since the Kichwa traditionally reserve most of their lands for primary and secondary forest stands, they do not have the range area available for cows and horses. The Kichwa people attribute their agricultural practices to two sources. First, their ancestors and elder relatives instilled in them the importance of maintaining primary rainforests for hunting regions and secondary forests to allow the soil to rest and repair itself for later agricultural use. And second, Kichwa people seldom have the capital necessary to fell large sections of forest; this requires either buying a chainsaw or paying hired laborers, the purchase of registered seed, and payments to laborers who plant the seed and return continuously with machetes to cut any native plants growing in the pasture.

Although they have incredible natural resources, the Kichwa people seek change: more contact with other cultures has been teaching them to judge their own lifestyles from an outsider perspective. They want to be part of the larger Ecuadorian economy and need to find ways to increase their annual family income of $600. They need cash to pay for their children's school tuition, school supplies, and uniforms. The Kichwa people have a vast pharmacopoeia of traditional healing plants, but sometimes it is necessary for them to seek medical help from the hospital in Tena. The hospital in Tena does not charge clients for services; but all supplies – needles, I.V. solutions, anesthetics, antibiotics, bandages, sutures, etc.—must be purchased by the patient or one of their family members at the neighboring pharmacy.

Thus far, handcrafts have proven to be an economic alternative that can help a large number of people without causing permanent and large-scale damage to the rainforests. Environmental devastation in the rainforest results from short-cycle agricultural crops that strip nutrients from the soil, making the land unfertile. Additionally, timber extraction completely destroys forests in a matter of a few years, resulting in soil erosion and lack of habitat for forest mammals and birds.

But it is oil companies who probably engage in the most devastating extraction practices in the rainforest. Over the past 50 years, the Amazon region has suffered countless blows from the oil industry's lack of responsibility. From 1967 to 1990, crude was extracted in Ecuador's Amazon jungle region only by Texaco. When it pulled out, several indigenous communities, with the support of environmental organizations, filed a lawsuit in the United States against that company for environmental damages. The plaintiffs demonstrated that in Ecuador, local rivers, flora and fauna were damaged because Texaco failed to use technology designed to protect the environment that is commonly utilized in other regions.

Oil companies do not follow the same regulations for extraction when drilling in other countries as they do in the United States. Without concern for the future of Ecuador's rainforest inhabitants, oil companies have devastated rivers, jungles, and wildlife, along with the health and culture of the Indigenous and Mestizo populations. Most recent studies carried out by the Center for Epidemiology and Community Health in Coca, indicate that there is a high incidence of cancer in communities near oil wells and toxic waste areas. Soils and rivers continue to be contaminated with these toxins in an area where most people are subsistence farmers.

The Kichwa people living in this rural poor region are asked to conserve their forest by outside conservation groups, and to give up their land and natural resources to multinational corporations—which take oil and profits back to their countries, leaving local people worse off with land that is unsuitable for horticulture and rivers full of contaminated fish. I have witnessed more evidence of pollution, deforestation, and destruction each year that I return to the Amazon, and have come to realize over time the urgency of assisting the Kallari project.

From Marketing Crafts to Promoting Public Awareness to Applied Anthropology

My involvement in the Kallari Handcraft Cooperative is three-fold. First, along with Heather Lloyd, an elementary education teacher who has also worked on the project for several years, I serve as the east coast crafts wholesaler. Heather and I have created an LLC called Global Expressions, which assists crafters in finding markets in the United States. I am in the process of aiding additional cooperatives in Latin America, including indigenous groups in Chile and Colombia.

Second, I have worked for the past four years promoting public awareness of Kichwa life and rainforest ecology, through presentations and publications for national and local organizations, e.g., the Society of Ethnobiology, the International Society of Ethnobiology, and the Society for Applied Anthropology.

Second, I have worked for the past four years promoting public awareness of Kichwa life and rainforest ecology, through presentations and publications for national and local organizations, e.g., the Society of Ethnobiology, the International Society of Ethnobiology, and the Society for Applied Anthropology.

Third, I have written my dissertation on the project. I found this project to be extremely innovative and to possess much promise for the future. One way that I was able to lend my expertise to the project was through closely studying the project using my academic anthropological training of participant observation, interviewing and surveying. I used these skills to assess the project over the past four years, as a viable economic alternative for the Kichwa people. My dissertation looks at the project to understand how local knowledge concerning non-timber rainforest products can be used as a renewable resource that aids in the preservation of rainforest and can also aid in the improvement in the quality of life of the Kichwa people. Development projects aided by anthropological methods of research into the social conditions within a particular area, have been shown to be more successful than those development projects without cultural assessments (Kottak). Anthropological assistance with development projects can aid in the management of natural resources, help assess the environmental consequences of development, as well as protecting endangered species (Gow). The three major functions of cultural anthropologists working on development projects are “ to collect and analyze information, help to design plans and policies, and to carry out these plans through action” (Gow).

I employed the theoretical framework of community-based conservation, which is a “sustainable use” and “bottom-up” approach to conservation. It focuses on conservation that begins at the local level and is concerned with finding a balance between local community land use and local natural resources. The reason for creating this balance is to attain sustainability, or the use of forest resources in non-destructive ways which allow for regrowth and regeneration of those resources for future use.

Community-based conservation also inquires into how the community fits into the long-term goals of the project. A “community” in this context consists of individuals who have different forms and amounts of power, as well as different secular motivations and religious beliefs. For community-based conservation programs to be effective, all of the people with rights or interests in a certain area —including local community members—must participate in agreements related to resource management. These “stakeholders” must identify particular resources and understand their need for protection as a whole (Singleton 2000).

My field research with the Kichwa involved spending time with people who would share their lifeways with me, so that I could understand Kichwa perceptions of the forest, plant utilization, and plant availability. From this information, I was able to identify and record their point of view regarding their local environment and the importance of their forest culturally, economically, and ecologically. Having this information will help assist in the overall growth and development of the project by taking into consideration the Kichwa worldview and the needs and desires of the local community.

Even though my dissertation fieldwork is now complete, I continue to work with this project today—helping to create public awareness of Kichwa culture, finding new markets for Kichwa goods, and promoting the idea of rainforest conservation and renewable resources. We work together on this project and are supported by others who are equally concerned with cultural survival and biodiversity conservation. We encourage other fair trade organizations and environmental supporters to contact us, as well as anyone who is interested in learning more about the Kallari project.

REFERENCES

Gow, David et al. 2002. Social Analysis for Third World Development: Toward Guidelines for the Nineties. Washington, D.C.: Development Alternatives/Institute for Development Anthropology.

Kottak, Conrad P. 1991. “When People Don't Come First: Some Sociological Lessons from Completed Projects”, in Michael M. Cernea (ed.), Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development. Oxford University Press.

Singleton, Sara. 2000. “Communities, States, and the Governance of the Pacific Northwest Salmon Fisheries. In Arun Agrawal and Clark C. Gibson (eds.), Communities and the Environment. Rutgers University Press.

Go to the GEO front page

Citations

Luci Latina Fernandes (2016). The Kallari Cooperative of Ecuador: Kichwa Artisans and Farmers Create Economic Alternatives in the Amazon. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/story/kallari-cooperative-ecuador

Add new comment