Thirty Years, and Four Phases of GEO

GEO's three decade journey is actually composed of four intriguingly distinct periods. Before there was GEO, there was the Changing Work magazine, and this had its own ancestry. And GEO itself appeared first as a hard copy newsletter, but has now become almost entirely digital. Of course, we may expect to find continuities along with the contrasts. But let's get started with GEO's own story, which began in the 1970s, even before it actually emerged.

GEO's three decade journey is actually composed of four intriguingly distinct periods. Before there was GEO, there was the Changing Work magazine, and this had its own ancestry. And GEO itself appeared first as a hard copy newsletter, but has now become almost entirely digital. Of course, we may expect to find continuities along with the contrasts. But let's get started with GEO's own story, which began in the 1970s, even before it actually emerged.

Before the Beginning (1975-1982)

This is the period of GEO's pre-history, before there was any sort of publication, or any sort of collective organization. In the mid-1970s a unique social movement came to life in the USA (and elsewhere), one that demanded that a strong, highly participatory form of democracy belonged in the workplace. Inspired in large part by the success of the Mondragon consortium of worker owned cooperatives, a small group of risk-taking pioneers came together to help create and support enterprises in which workers – rather than outside investors or government bureaucrats – had the final say on all major decisions.

The four eventual founders of Changing Work – Chuck Turner, Frank Lindenfeld, George Benello, and Len Krimerman – were all part of this group of workplace democracy pioneers. They had helped found two organizations, the Federation for Economic Democracy (FED), and the Industrial Cooperative Association (ICA) with specific missions to support worker owned and controlled businesses. And by the early 1980s, they had accumulated a whole lot of very practical experience attempting to actualize their common vision. Chuck was serving then as ICA's education coordinator; Frank had coordinated the Philadelphia chapter of FED, and was assisting the sugar cane cooperatives in Jamaica; George was the driving force in FED, and was a founding board member of ICA; and Len was on the board of ICA, and had helped start and worked in the International Poultry cooperative in eastern Connecticut.

All in all, though, they felt – in the early 1980s – that the movement still lacked a real sense of itself, and of its own potential. There had been three conferences on "democratic business" at Guilford College in North Carolina. But beyond this, there was little communication, sharing of lessons and experiences – much less, collaboration – among its overwhelmingly isolated enterprises. And even less with like-minded initiatives outside of the eastern coast of the USA, or in other countries.

How better to fill this gap but through a magazine dedicated to publicizing workplace democracy and to building the movement's fuller sense of itself?

Changing Work: A Magazine to Make the Vision Public (1983-1990)

Actually, just before there was Changing Work: A Magazine about Liberating Worklife, there was a year's worth of regular columns in the Planners Network Newsletter(PNN), entitled "Round-up: Worker Co-ops, Employee Ownership, and Workplace Democracy". These occupied roughly a page per issue of PNN from June, 1983 through August, 1984, each carrying seven to ten very brief accounts of initiatives, events, and resources "gleaned from an emerging network of people and groups concerned with democratizing the workplace through worker co-ops, employee ownership, and democratic participation." (PNN: 6/20/83)

Actually, just before there was Changing Work: A Magazine about Liberating Worklife, there was a year's worth of regular columns in the Planners Network Newsletter(PNN), entitled "Round-up: Worker Co-ops, Employee Ownership, and Workplace Democracy". These occupied roughly a page per issue of PNN from June, 1983 through August, 1984, each carrying seven to ten very brief accounts of initiatives, events, and resources "gleaned from an emerging network of people and groups concerned with democratizing the workplace through worker co-ops, employee ownership, and democratic participation." (PNN: 6/20/83)

Eventually, the gleanings became more and more numerous, and the stories they told were too good to be compressed into a short paragraph or two. Instead, a group of them were gathered up in full form, photocopied, and put into a few dozen loose-leaf binders. These were then handed out as a prototype during the April, 1984 Conference on Employee Ownership and Workplace Democracy in Washington, DC. The feedback was extremely positive, and Changing Work(CW) was born; its first print issue, 68 pages based on the prototype, appeared in November of 1984.

Some key features of this second period include: regular and practical departments (Postal Exchange: Letters from Readers; News and Notes; Finding Funding; Corporate Watchdog; Resources; Calendar); interviews and forums featuring hands-on practitioners; a very wide range of writers – geographically, from rank-and-file co-op owners to well established authors, and from numerous countries and social movements. And almost always, these were enhanced by photos, original graphics, and, often, by poetry. This list of a few CW articles may give a sense of its wide range:

- "Political Education for Worker Management", by George Benello: "education that extends beyond the self-managed firm and can serve to bind workers together into a movement for worker self-determination." (Winter, 1988)

- "Home Grown Roundup; Six Short Takes on How Communities are Building Self-Reliance", together with "Resources for a Home Grown Economy" a pullout Directory with working models, for local organizing (Spring, 1986)

- "The Wages for Housework Campaign" by Mary Hawryshkiw of the International Wages for Housework Campaign (Winter/Spring. 1987)

- "A Weavers Tale: Connecting Past, Present, and Future", by Andrea Cesari: "…when we practice traditional crafts, we also regenerate the craft, transforming it from an historical relic into a vital skill to which we contribute our own work and creativity." (Fall, 1988)

- "The Genesis of the Idea of a Community Right to Industrial Property in Youngstown and Pittsburgh, 1977-1987", by Staughton Lynd: "Instead of regarding ownership [of productive enterprises] as an indivisible package of rights, " Staughton wrote, "we regard it as a bundle of rights some of which can be retained by the community for its own protection." (This article was one of two dozen pieces contributing to a celebration and assessment of the workplace democracy movement's accomplishments in the 1980s.)

- "EUROSCENE: Gabrielle Herbert reports on "Co-op 84", a London gathering representing over a thousand cooperatives: "The first European [Cooperative] Fair was an important step in the promotion of cooperative infra-structure. It provided the possibility of communication among people who represent different approaches, different towns, and different countries. Unfortunately, the Fair was weakened by the lack of representation from most European countries." (Fall, 1984)

- "Steel Voices – The MillHunk Herald Saga", by Larry Evans: Larry described the Herald as a "sort of microcosm of what an unleashed worker's self-educative movement might look like." Two of the Herald's poems were published along side of his article.)

Why such an unusually broad range? The Editorial Preface to issue #1 provides an answer:

Why another magazine? How will Changing Work be different?....

[It} has distinctive aims: to provide a forum for sustained dialogue on the goals and strategies of reconstructing work (e.g., on how worklife can be made not only more democratic, but a source of joy and creativity); to help build solidarity among the often disconnected groups seeking to increase democracy at work; to foster alliances between these groups and others with allied goals, such as labor, ecological, and health care groups; and to develop collaboration on changing work across national boundaries.

These aims, as we shall see, remain a constant compass throughout the rest of GEO's history. And they remain goals very largely unfulfilled. In an important recent article, Marjorie Kelly tells us that:

Emerging in our time—in largely disconnected experiments across the globe—are the seeds of a different kind of economy. It, too, is built on a foundation of ownership, but of a unique type. The cooperative economy is a large piece of it. But this economy doesn't rely on a monoculture of design, the way capitalism does. It's as rich in diversity as a rainforest is in its plethora of species—with commons ownership, municipal ownership, employee ownership, and others. You could even include open-source models like Wikipedia, owned by no one and managed collectively.

These varieties of alternative ownership have yet to be recognized as a single family, in part because they've yet to unite under a common name. We might call them generative, for their aim is to generate conditions where our common life can flourish. Generative design isn't about dominion. It's about belonging—a sense of belonging to a common whole. ("The Economy: Under Different Ownership": Yes! Magazine, Spring, 2013.)

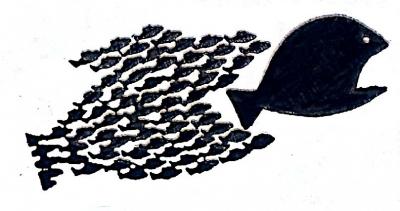

Yes, two decades after CW first appeared, alternatives to capitalism (or within it?) are often still "disconnected experiments". A common name, like "generative", for these alternative economic designs might well help some. But it won't take us very far towards supplanting capitalism: as CW maintained, "alliances", "collaboration", and "building solidarity" across organizational and geographical lines and contrasting priorities will be required. Otherwise our diverse rainforest-like movements, regardless of their adoption of a common name, will remain easy prey for the mono-cultural and dominant economy.

CW was very widely respected, but, we found, not often read. Our issues averaged over 60 pages, and a very typical comment was, "This is great stuff, but I don't have time to read it." In 1989, we printed two final issues presenting a wide-ranging forum on "Celebrating a Decade of Democracy at Work". The idea was to crystallize what the diverse elements in the workplace democracy movement had learned in the 1980s, and what they saw as needed in the 1990s. We then closed down CW, and began to rethink what this magazine had taught us, and to re-imagine our own mission and next steps. Part of that internal process led directly to two published anthologies, When Workers Decide and From the Ground Up, both of which utilized articles originally published in CW.

But another outcome of that process led to GEO, the Grassroots Economic Organizing Newsletter (and collective).

Less is More: CW Morphs into the GEO Newsletter(1991-2006)

By 1990, co-founder George Benello had died, a victim of medical malpractice, and Chuck Turner had returned to community and labor union organizing. Undaunted, Frank and Len again produced a prototype, this time for a newsletter that would fill no more than 16 pages and usually only 12. Articles would be shorter, 1500 words at the max, and often only 500-1000. Feedback was again sought, this time from many CW co-conspirators and subscribers. It being mainly positive, the new slimmer and even more practical newsletter began publishing in November, 1991.

By 1990, co-founder George Benello had died, a victim of medical malpractice, and Chuck Turner had returned to community and labor union organizing. Undaunted, Frank and Len again produced a prototype, this time for a newsletter that would fill no more than 16 pages and usually only 12. Articles would be shorter, 1500 words at the max, and often only 500-1000. Feedback was again sought, this time from many CW co-conspirators and subscribers. It being mainly positive, the new slimmer and even more practical newsletter began publishing in November, 1991.

The masthead for this first issue reveals the range of those listed as "contributing editors": from Africa, the Basque Country, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Germany, and Japan, as well as Washington state, Utah, Texas, Maine, Illinois, and elsewhere in the USA. Radical economist Germai Medhanie, originally from Eritrea, had joined Frank and Len as an "Editorial Coordinator", and the issue's major articles included an account, with a comic graphic, of the Japanese Seikatsu Cooperative Club, based on information supplied by contributing editor Shuei Hiratsuka, then general manager of the club's Tokyo branch. At that point, Seikatsu had 204,000 members and had developed "himawari" (roughly, "mutual aid") cooperatives based on community forms of barter, to fill significant gaps left by the Japanese public welfare system. (Himawari, so like hour exchanges or time banks, seems like a great idea. But where is Seikatsu now? Yvonne Poirier follows up with them here.

Another main article in GEO #1 was an interview of Michael Locker, then a consultant to the USWA, in particular on union-led worker buyouts or employee ownership. (Is history repeating itself? Why did this 1990s strategy cool down after just a few years; will the new version be able to learn from, and avoid, whatever subverted the older one?)

On the whole, there was plenty of content continuity with CW; e.g., on exemplary cases of coalitioning or, later, inter-cooperation, among a wide range of democratic and progressive organizations. But there were contrasts as well: youth initiatives and education in democracy were highlighted in perhaps ten different issues of GEO, but rarely mentioned in CW, and some topics CW returned to repeatedly – economic conversion, the need to de-militarize the economy, re-industrialization of the rust belt – were largely ignored in GEO. All in all, coverage of global grassroots initiatives outside North America and Western Europe – in Brazil, Mexico, India, and Africa was deeper and more frequent in GEO than it had been in CW. This resulted in part from having more issues each year, but also from the wider experience brought into GEO by a host of new "coordinators". These included Wade Wright, Betsy Bowman, Bob Stone, Ken Estey, John Lawrence, Ethan Miller, Bill Caspary, Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Ajowa Nzinga Ifateyo, and Jim Johnson....

Another sort of contrast with CW began to emerge around 1997, with issue #26, which featured Bob Stone's article on Inter-Cooperation & the Co-op Movement, A Proposal. CW's founders and early coordinators of GEO combined both activism and reflection, practice and theory. And this was certainly continued by new core members. But those new folks shaped their activism – and eventually that of the whole GEO collective – in very concrete and novel ways. That is, they ventured to help bring a USA-based movement to a new and stronger level by bringing together enterprises that had previously functioned "in splendid isolation". For example, Bob Stone (and his son Mike) traveled throughout the northeast as ambassadors of "regional associations and inter-cooperation"; groups like the Pioneer Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives began to form as an indirect result. Others like Jessica and Ajowa, along with Bob, assisted the formation of the Eastern Conference for Workplace Democracy in 2001, and have been active voices within it, as well as the national United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives (USFWC), formed in 2006. In 2000, GEO published "An Economy of Hope", the first directory of USA worker cooperatives, with contact information and brief descriptions of about 350 entries. This in turn laid a partial foundation for the recently incorporated Data Commons Cooperative, in which GEO is still a member. DCC can provide far more detailed and nuanced information than our initial directory, as well as a marvelous map, of almost 1000 organizations, a number which just keeps on growing.

In short, by 1997 GEO's activism – so it seems to me – began to take a much more focused form than that of its predecessor; as a result, we tangibly contributed to the growth and maturity of the workplace movement in this country. CWers advocated and educated, and helped build isolated alternatives, but GEO went further, becoming more like organizers or catalysts, not just walking our talk, but helping to create the path on which others would walk together.

GEO.COOP: Virtual and Freely Accessible to All (2007-present)

Since 2007, GEO has produced 14 digital issues; one of them has also appeared in hard copy. Appropriately, the first of these announced:

Since 2007, GEO has produced 14 digital issues; one of them has also appeared in hard copy. Appropriately, the first of these announced:

Welcome to the first official issue of GEO's new electronic newsletter. We close the past twelve (sic!) years and 77 issues (volume 1) and open a new volume in our work of sharing stories of hope, creativity and vision in the work of building a just, sustainable and democratic society.

In contrast with both CW and Volume 1 of GEO, there is no fee to access the website, nor to start and maintain one's own blog (subject to certain guidelines). Subscribers can freely sign up to receive email blasts and other communications via an email newsletter. We are in addition busy digitizing all of our GEO issues – about half are already accessible in our web archives – and are working out the details for doing the same with the eight years of CW issues. And with the expertise of Marty Heyman, one of our newest members, we will very soon be offering e-books of several of our virtual issues. All of these are certainly steps forward, beyond what the early phases of GEO could achieve.

The range of issues covered has remained wide, risk-taking, and provocative, including:

- #11, coordinated by Ajowa Nzinga Ifateyo, in which GEO explores the legacy, and lessons, of John Howard Griffen's Black Like Me, a book written five decades ago which "stunned white America with a truth it did not want to see: a virulent, soul-killing racism against African people within this reputed 'democracy'."

- #10, coordinated by Ethan Miller, a "seven part series inspired by, and written for, the Occupation movement", in which he addresses the key question, "as we condemn the economy built for the benefit of the 1%, what do we want in its place, and how will we build it."

- #9, coordinated by Michael Johnson, which provocatively brought together practitioners and researchers who focus on "cooperation" and revealed just how much each side of this equation can learn from discussing their common work together. The issue was introduced by Nobel Prize economist Lin Ostrom, and several of her former students contributed articles based on their own research. Lin, who left us just last year, was perhaps the pre-eminent researcher into the many diverse forms of self-reliant and cooperative group action people are actually using to shape their economic lives, and to escape the control of both government bureaucracies and corporate hooligans.

- #13, coordinated by Len Krimerman, the Frank Lindenfeld Memorial issue, dedicated to our beloved co-founder of both CW and GEO. Filled with heart-felt "Remembrances and Memories", some dating back to the 1960s, when Frank ran a "free school" in California, others from Frank's work in the 1980s with sugar cane cooperatives in Jamaica, and still others from his comrades in GEO and in the Association of Humanistic Sociology. Some of his written work is included as well, including the seminal and still-timely "Cooperative Commonwealth" (together with comments on it from Michael Johnson and Bob Stone).

Becoming virtual did not prevent us from further refining our activist mission. Instead, core members of GEO, and in particular Michael Johnson – who had joined us in 2007 – initiated an ongoing process we have called "Advancing Worker Cooperative Development"(AWCD).

This process was first introduced in 2011 at the ECWD Conference in Baltimore, where some 60-70 participants, with often deeply divergent notions of how to develop worker co-ops, listened, argued, and listened again to one another.

In 2012, AWCD was utilized in Boston at the USFWC Conference with an even larger group of co-op practitioners and developers. And in July, a new version of the process – focused on self-financing of co-ops – will take place in Philadelphia, at this year's ECWD Conference. (For the program and to register, go to http://east.usworker.coop/.) In all three cases, AWCD has been presented as a "mini-conference" before the association's conference, so that participants could focus in depth on the issues being raised, ones that often quietly separate or weaken the movement, but have been largely ignored.

What's Next For GEO?

I wouldn't dare make a prediction; what's next will flow from what is happening now, as well as from the mosaic of our past, sketched above. But – always – in a spontaneous, less than controllable, manner. The three new articles in this issue are suggestive of emerging grassroots initiatives on which we may concentrate some of our energies.

Beyond this, though, there are the many, many wonderful, sad, encouraging, lesson-providing stories we have covered in our first three decades. These merit revisiting. One could spend time far worse than by mining these and extracting from them not only what's "worked" and what has not, but the richness and freshness of this still very young movement towards a democratic worklife, and using that to remind it where it has been and how miraculous a role within an otherwise vicious and rapacious world it has begun to play.

We're looking for a few sympatico souls to join with us in this endeavor of collective memory. Contact Len at editors@geo.coop, if you are at all interested, or want more information.

Citations

Len Krimerman (2013). Chronicling the Chronicler: Thirty Years, and Four Phases of GEO. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/story/chronicling-chronicler

Add new comment