[Editor's note: J Rainsnow is a novelist. His unusual review of Bulding Co-operative Power: Stories and Strategies from Worker Co-Operatives in the Connecticut River Valley comes from an artist’s perspective, outside of that of most co-operators, organizers, and activists. His view is large and his grasp of details surprisingly rich. This review is cross-posted from his blog. He and Michael Johnson, one of the co-authors of the book and a member of the GEO Collective, know each other.]

Sort of a book review (I don't straight-shoot anything)...

When I first began writing The March of the Eccentrics, it was because I was propelled by a crazy imagination which I could not resist, any more than a rocket can resist the flame coming out of its back ("like it or  not, you're going to the moon"); and because I wanted to have a positive influence on the world. I wanted to inject a new dose of revolutionary culture into the world - characters who would inspire, trigger, lift and launch the slumbering and the demoralized, the dormant and the unknowing; stories which would lead people who were tired of reality back to reality, refreshed and reinvigorated by a new mythology; fantasy back-doors into truth which would bypass the daunting parapets of depressing newspaper articles and the numbing moats of unbearable television footage, which inspired retreat from what was happening just as much as engagement. It was my hope to create a diversion from reality which would use reality (mixed with an alluring measure of fantasy) as its raw material, and which, instead of leading to a permanent detachment from reality, would re-energize us and resurrect our ability to face it anew. My fantasy world was always meant to be connected with the real world: to be joined with those who were fighting, with those who were struggling, with those who were dreaming with tools in their hands, actually putting together the bricks of a new day.

not, you're going to the moon"); and because I wanted to have a positive influence on the world. I wanted to inject a new dose of revolutionary culture into the world - characters who would inspire, trigger, lift and launch the slumbering and the demoralized, the dormant and the unknowing; stories which would lead people who were tired of reality back to reality, refreshed and reinvigorated by a new mythology; fantasy back-doors into truth which would bypass the daunting parapets of depressing newspaper articles and the numbing moats of unbearable television footage, which inspired retreat from what was happening just as much as engagement. It was my hope to create a diversion from reality which would use reality (mixed with an alluring measure of fantasy) as its raw material, and which, instead of leading to a permanent detachment from reality, would re-energize us and resurrect our ability to face it anew. My fantasy world was always meant to be connected with the real world: to be joined with those who were fighting, with those who were struggling, with those who were dreaming with tools in their hands, actually putting together the bricks of a new day.

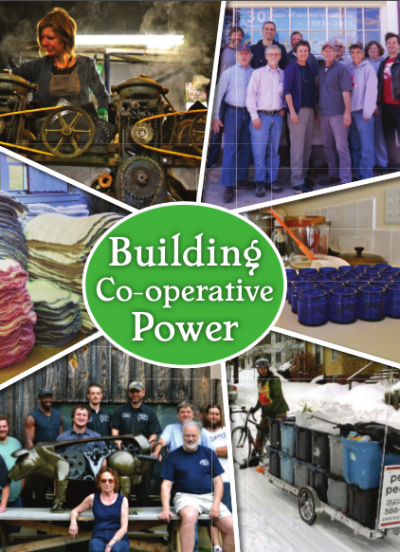

This understood, it should not be surprising that I have undertaken to 'review', or better said, 'bring up', or 'publicize' a humble yet hopeful little book by the name of Building Co-operative Power, authored by Janelle Cornwell, Michael Johnson, and Adam Trott, with Julie Graham (Amherst, Mass: Levellers Press, 2013). It is a book which describes people who are attempting to build a new day, not by waving brightly-colored flags around and beating on drums in the middle of the street (nothing against that so long as there is more than just the show), but by meticulously and with great determination working, day by day, to create the structures, foundations, understandings and behaviors which will not only make their own lives more rewarding and in tune with the principles which most people profess but few manage to live by, but could also, conceivably, one day plant the seeds of a major shift in the way the world's heart beats and the world's lungs breathe. Although Building Co-operative Power seems to deliberately curtail that emphasis, it suggests it more discreetly. It avoids the grandiose, but its sober and careful analyses of small-scale, nuts-and-bolts operations of transformation do define and map out potential building blocks of a new kind of civilization: one in which there is peace between labor and capital; one in which fairness, justice, sustainability, health and well-being are major factors in the planning and running of the economy; one in which humanity is not swallowed up by the processes ostensibly created to benefit it, but remains in true control of its destiny and future.

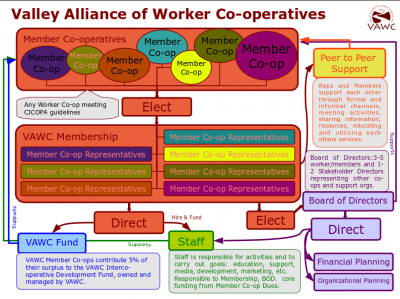

To break it all down: Building Co-operative Power attempts to do several things at once. It provides, on the basis of interviews, protagonist-self-explanations, and author research and assessments, a close-up view of several worker cooperatives in the Connecticut River Valley, as well as a look into the Valley Alliance of Worker Co-operatives (the VAWC), a larger coordinating and connecting organization which has come into being to represent and assist these co-ops, and, where possible, to extend and strengthen the phenomenon begun by them. Building Co-operative Power also attempts to provide a framework for understanding worker cooperatives in general, and beyond that, all types of cooperatives (for example, producer cooperatives and consumer/user cooperatives); to clarify the nature of worker cooperatives, and the challenges inherent in building and maintaining them; to study the nature of the difference between these co-ops and mainstream business models, as well as the nature of the relationship between these co-ops and society at large; and to point out the benefits of cooperative systems and to advocate for them, in an effort to break through society's disempowering lack of awareness regarding them (you don't let in what you don't understand) and to also move cooperatives, themselves, towards a higher level of inter-co-op cooperation, in order to magnify their impact and enhance their survivability.

To break it all down: Building Co-operative Power attempts to do several things at once. It provides, on the basis of interviews, protagonist-self-explanations, and author research and assessments, a close-up view of several worker cooperatives in the Connecticut River Valley, as well as a look into the Valley Alliance of Worker Co-operatives (the VAWC), a larger coordinating and connecting organization which has come into being to represent and assist these co-ops, and, where possible, to extend and strengthen the phenomenon begun by them. Building Co-operative Power also attempts to provide a framework for understanding worker cooperatives in general, and beyond that, all types of cooperatives (for example, producer cooperatives and consumer/user cooperatives); to clarify the nature of worker cooperatives, and the challenges inherent in building and maintaining them; to study the nature of the difference between these co-ops and mainstream business models, as well as the nature of the relationship between these co-ops and society at large; and to point out the benefits of cooperative systems and to advocate for them, in an effort to break through society's disempowering lack of awareness regarding them (you don't let in what you don't understand) and to also move cooperatives, themselves, towards a higher level of inter-co-op cooperation, in order to magnify their impact and enhance their survivability.

In the end, the book seems to direct its final focus towards the goal of promoting and strengthening the co-op movement in the Connecticut River Valley, which would make it seem to be a local piece, something beautiful but limited like "arts and crafts from Alameda County", or "novels written by residents of Jackson Heights." However, the discussion in the book is wide-ranging (even taking us abroad to Italy and Spain), and the lessons to be learned from the cooperative struggles and triumphs in the Connecticut River Valley are clearly useful and applicable on a much wider scale, certainly throughout the U.S.A. It also seems clear, between the lines, that the authors of the book are drawn to the activity in the Connecticut River Valley not just because they live there or within driving distance of it, but because there is some kind of collaborative buzz there, something palpable, and hope-creating: in the Connecticut River Valley, they have found a promising hub of cooperative activity which, perhaps with a little extra nudge (and certainly some more time), might one day start rolling towards the kind of 'critical mass' needed to generate something powerful and expansive, like the attainments of Mondragon in the Basque region of Spain, which are repeatedly referred to. Such a powerful development in such a culturally visible and influential region of the US (East Coast, in range of Boston and New York City) could, in turn, begin to engage the rest of the country in a shift towards new concepts of business management, ownership, priorities and concerns, which could, in turn, have a revolutionary and humanizing effect on the nature of our civilization, itself. That's something we sure could use at a time like this: a time when the integrity of our democracy, the fate of justice throughout the world, and even the survival of the earth itself, victimized by our human lack of vision and self-control, seem at risk! (Not to be melodramatic, just keeping it real...)

This having been said, I won't go on to exhaustively chronicle Building Co-operative Power, but stick to bringing up a few of my favorite points from it.

But before that, I suppose, we need to be clear on the basic subject matter of the book: the co-operative, itself! What is it? The authors describe three basic types of cooperatives: producer cooperatives (such as farmer co-ops); consumer, or user cooperatives (such as food co-ops, or credit unions); and worker co-ops, which are the main (but far from exclusive) focus of the book. (These three types of co-ops are referred to as sectors, while the term industry is used to differentiate between the specific areas of cooperative endeavor, such as printing, textiles, retail/bookstore, etc.) In the worker cooperative, the enterprise is owned by the workers, and not by capitalist entrepreneurs or investors dedicated to their own profit above the well-being of the workers (who in the classic capitalist business model are envisioned as components of the profit-generating scheme and not as its principal benefactors). Neither is the worker cooperative a cog in a bureaucratic socialist milieu (such as the old-school USSR), in which the ideal of the worker's primacy is merely a myth at the service of a heavy-handed and domineering political-managerial class.

In the worker's cooperative, as it exists and is conceived of in the US and in many other places throughout the world today, the workers are no longer pawns who are pushed across the board by someone else: they make their own moves. They are bosses, they are in control; they are worker-owners. They create their own management structures and direct themselves, participate in making important business decisions affecting the company and its members, set their own objectives, determine (according to their economic understanding and personal and moral priorities) what they will produce, how much, and for what price, and how the surplus generated by their activities will be distributed among members or invested in the company or community. All of this has huge potential ramifications for both individual and society.

In the worker's cooperative, as it exists and is conceived of in the US and in many other places throughout the world today, the workers are no longer pawns who are pushed across the board by someone else: they make their own moves. They are bosses, they are in control; they are worker-owners. They create their own management structures and direct themselves, participate in making important business decisions affecting the company and its members, set their own objectives, determine (according to their economic understanding and personal and moral priorities) what they will produce, how much, and for what price, and how the surplus generated by their activities will be distributed among members or invested in the company or community. All of this has huge potential ramifications for both individual and society.

The individual who works for the cooperative is empowered, which is humanizing, not mere 'cannon fodder' for creating someone else's wealth as often happens in classic business enterprises; he/she is more likely to get a fair wage (an unbalanced portion of the surplus is not siphoned off and directed to non-worker managers, entrepreneurs and investors as profit); and he/she is more likely to experience a sense of (and reality of) job security, since the cooperative is not geared to treat its workers as expendable factors, to be shed in 'cost-effective' streamlining operations in times of hardship. (At such times, the cooperative is far more likely to struggle for solutions which will enable its members to remain aboard). For society, the co-op is also highly beneficial, since raw 'profit motive' is not built into its design, and the state of mind fostered by and necessary for its operation tilts it towards the bigger picture, towards collaboration with others, and towards responsible belonging within the larger social group. It seems that many worker's co-ops actually orient themselves towards providing extra services/discounts/and/or investments in the wider community of which they are a part.

One point I really loved, as the authors developed their arguments, was this one: Today, we live in what has been termed a 'thin democracy', meaning a society in which 'democracy' for the average man has boiled down to little more than voting in elections - choosing officials who will lead us (or drag us behind them until the next election): a pretty hollow form of political inclusion, though certainly better than nothing. Meanwhile in the classic workplace, where we spend much of our lives and where our fate hangs in the balance (for without our wages we will be cast down to new levels of adversity), there is no democracy. We are essentially exposed to an autocratic environment which not only affects our sense of worth and security, but also de-conditions us to the skills and values vital to the health and preservation of our democratic system. In the worker's co-op, that changes. In the crucible of this alternative business model, the 'good citizen' is encouraged to grow and is, in cases, reconstructed by experience and practice: the 'good citizen' who is communicative, involved, able to express ideas, to compromise, to overcome personal differences and forge common paths, to push forward past the sparks instead of closing up or leaving, to weave different outlooks into a coherent whole; the 'good citizen' who is the essential raw material of a survivable democracy, and surely one of the greatest products any enterprise could ever manufacture!

The authors of Building Co-operative Power effectively convey to us the benefits of worker co-ops over traditional business models. But they are also absolutely clear in emphasizing the hard work involved in forming and running them in a society which is geared towards recognizing and encouraging traditional business models, and which does not necessarily prepare us, as individuals, for the responsibility and person-to-person skills necessary for cooperating with others in place of commanding and following others. Some of the difficulties associated with getting worker co-ops off the ground, and keeping them up (as well as many of the successes and benefits of the process), are crystallized in the book's substantial and very helpful section on specific worker co-ops of the Connecticut River Valley. These sections are written by co-op members themselves, with review or commentary provided as needed by the authors. Among the co-ops portrayed are: Common Wealth Printing, Collective Copies, PV Squared (solar-panel installation), Pedal People (bicycle-powered trash-collectors), GAIA Host Collective (web and email hosting), Green Mountain Spinnery (yarn producer), Co-op 108 (natural body products), Valley Green Feast (food delivery service connecting customers with local farm produce), TESA/Toolbox for Education and Social Action (educational materials and games to promote a progressive social vision), Brattleboro Holistic Health Center, and Simple Diaper and Linen (biodegradable disposable diapers and conventional diaper laundering service). The stories are engaging and instructive, and add personality to a book which otherwise might become too theoretical and technical. Put together with the theory, a nice balance is struck, and a compelling 3-dimensional picture of worker co-ops fleshed out.

Besides these points, I also found the authors' discussion of "invisibility" quite important and interesting. According to the authors: "Together, consumer, producer and worker co-ops comprise a substantial fraction of the world economy. One billion members of co-operatives are providing 100 million jobs worldwide. Even the U.S. - a pillar of capitalist profit and culture - is home to some 30,000 co-operatives  operating in 73,000 places of business, managing $3 trillion in assets, $500 billion in revenue and $25 billion in wages." (p. 170) In light of these impressive figures, how is it possible that the existence of cooperatives is so underperceived (even by many people who are directly benefiting from them!); how is it possible that a phenomenon so tried and tested is still treated as if it were something novel and fringe, a dangerous new innovation likely to go off the road and crash, a pipedream of lunatics, or utopian wet-dream? It is as if the successes and viability of many such co-ops and the substantial track record already established by them were draped in a cloak of invisibility, obscuring the cooperative option and removing it from the national economic conversation. With but a few exceptions, business schools and universities do not offer courses or training regarding the cooperative option. Many state laws and state bureaucracies do not easily facilitate their creation (they anticipate that businesses will be formed along the classic lines of the sole proprietorship, the partnership, the LLC, and the corporation.) The public, often not aware or in proper understanding of the "co-operative difference", is not always engaged to support co-ops and nurture what they represent, in spite of the potential payback for society.

operating in 73,000 places of business, managing $3 trillion in assets, $500 billion in revenue and $25 billion in wages." (p. 170) In light of these impressive figures, how is it possible that the existence of cooperatives is so underperceived (even by many people who are directly benefiting from them!); how is it possible that a phenomenon so tried and tested is still treated as if it were something novel and fringe, a dangerous new innovation likely to go off the road and crash, a pipedream of lunatics, or utopian wet-dream? It is as if the successes and viability of many such co-ops and the substantial track record already established by them were draped in a cloak of invisibility, obscuring the cooperative option and removing it from the national economic conversation. With but a few exceptions, business schools and universities do not offer courses or training regarding the cooperative option. Many state laws and state bureaucracies do not easily facilitate their creation (they anticipate that businesses will be formed along the classic lines of the sole proprietorship, the partnership, the LLC, and the corporation.) The public, often not aware or in proper understanding of the "co-operative difference", is not always engaged to support co-ops and nurture what they represent, in spite of the potential payback for society.

The hypnotic power of the mainstream economic model, and the inertia of our culture and its official history and mythology, have simply trained our eyes to look the other way and to see the preferences of the powerful and the entrenched, which blind us to choices less conventional - to choices less centrally located on the map of lauded triumphs, yet every bit as legitimate and functional. As a consequence of this 'invisibility', co-ops and the cooperative movement are denied much of the human energy, belief, commitment, patronage, and training, and many of the investment opportunities and foundational skills necessary for their proliferation and transition into a more widespread and influential model for business development/social evolution.

To break through this barrier, many worker co-ops in the Connecticut River Valley have joined forces through the VAWC, which is committed to helping support the creation and promotion of new worker cooperatives, and to channeling crucial advice and experience to member co-ops in order to help them prevail over the inevitable obstacles. (Why reinvent the wheel every time, especially when it is such a complicated and potentially self-imploding experience?) In the same vein, efforts are being made to educate consumers and students alike - consumers who will realize the benefits and greater cultural prospects of the co-op and especially patronize it for that - and students who may come to fill the ranks of the next generation of economists and business owners: a new generation open where the previous one was closed. Besides this, the different sectors of co-ops are initiating efforts to come together - to build new levels of inter-co-op cooperation - as manifested by the creation of the VCBA (Valley Co-operative Business Association), which combines members of producer, worker, and consumer co-ops, and which is seeking to develop links between them and to enhance their connections with the public.

To break through this barrier, many worker co-ops in the Connecticut River Valley have joined forces through the VAWC, which is committed to helping support the creation and promotion of new worker cooperatives, and to channeling crucial advice and experience to member co-ops in order to help them prevail over the inevitable obstacles. (Why reinvent the wheel every time, especially when it is such a complicated and potentially self-imploding experience?) In the same vein, efforts are being made to educate consumers and students alike - consumers who will realize the benefits and greater cultural prospects of the co-op and especially patronize it for that - and students who may come to fill the ranks of the next generation of economists and business owners: a new generation open where the previous one was closed. Besides this, the different sectors of co-ops are initiating efforts to come together - to build new levels of inter-co-op cooperation - as manifested by the creation of the VCBA (Valley Co-operative Business Association), which combines members of producer, worker, and consumer co-ops, and which is seeking to develop links between them and to enhance their connections with the public.

Finally, of course, we have this book, itself - Building Co-operative Power - which is also a part of the effort to place the co-op movement (in the Connecticut River Valley, but via extension, throughout America), onto the social radar screen; to raise public awareness regarding the existence and worth of co-ops; and, in its way - with patience and methodicality in place of glamour - to advance the cause of cooperative development, and the human progress which will intrinsically accompany it. Let's give thanks to the protagonists of the book for their consciousness and sweat! And let's give thanks to the authors of the book for their commitment to bring that story to light, and in so doing, to shine a light on new possibilities for all of us.

Although my novel, The March of the Eccentrics, is about as different in style and presentation as can be imagined from Building Co-operative Power, the latter being a sober, careful study well-grounded in the practical and focused in scope, the former being a wild idiosyncratic act of the imagination careening across an alternative-reality globe, both works meet on the common ground of envisioning a future of justice and hope for all human beings. My book seeks, through fiction, to raise the spirit and arouse the imagination that will support the changes the world needs. Building Co-operative Power portrays real-life men and women actually working on those changes, one humble yet meaningful day at a time; and it invites us to add our weight to the movement they have begun in order to build, from the ground up, a new world founded on the values of cooperation, non-exploitation and human empowerment.

Download the introduction of Building Co-operative Power

Purchase Building Co-operative Power from Levellers Press

Go to the GEO front page

Add new comment